On the Opossum Trail

There is a place I know,

Covered in Cedar trees.

Down where the river flows.

That’s where I want to be.I don’t care if it’s raining,

I’m not gonna stay inside.

I just want to run through the forest,

And see where the creatures hide.- There Is A Place I Know by Carly Joynt

For the past few years I have been tracking the Scout Camp beside where I work. I have gone there with tracking clubs, on my own, and most often with students. Lately with the students, we trailed an Opossum (Didelphis virginiana) around the area. We followed them around the Torrence Creek, along an old barbed wire cow fence, and then finally into a small opening at the base of a large Eastern White Cedar (Thuja occidentalis) root matt. The tracks went in and there were no trails leading out. We checked out the hole with a flashlight, but saw nothing but debris. I was hoping to find some scat while we trailed them, which this is notoriously hard to find, but while we didn’t it was still a great adventure overall, getting the kids trailing across and through the creek, over tangles of fallen Common Buckthorn (Rhamus cathartica) and sprays of Privet (Ligustrum vulgare), over and under the barbed wire, all to follow the confusion of an Opossum trail.

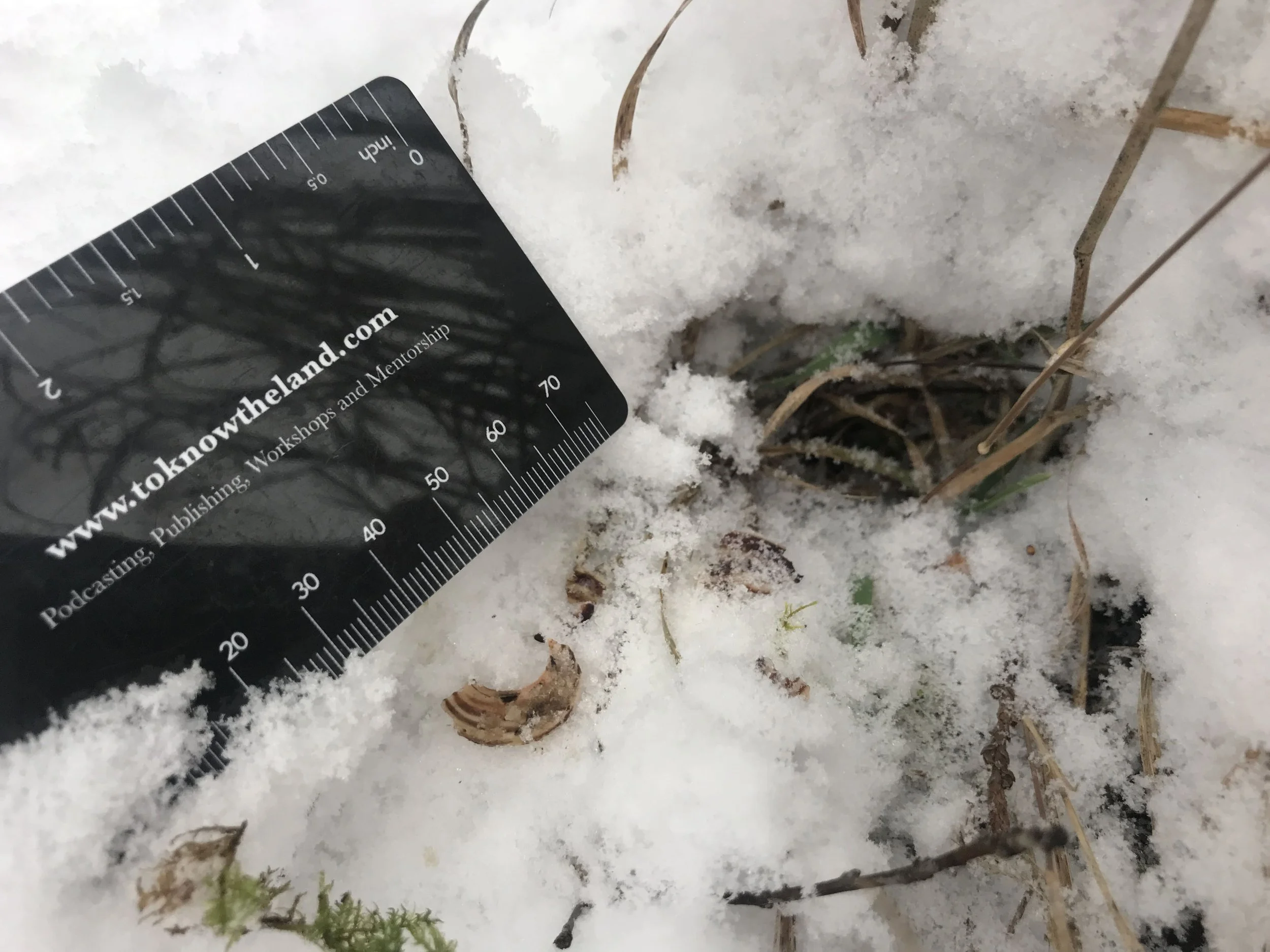

Left front below and hind above, like a foggy sunrise over a valley.

Today, with the newly fallen snow, and warmer weather (around -1°C, or 30.2°F), it seemed like the perfect day to go back and try to pick up a trail again and see what I could learn.

I ended up picking up on an Opossum trail fairly quickly along the trail. It was the same area within a few meters of the spot where I had been trailing the Opossum a couple of weeks ago with my Monday students. In retrospect I wish I had measured the tracks thoroughly to start trying to see if this is the same individual, but I did not. I did measure the stride length and it was between 19 - 24 cm (7½ - 9½ in), with the 24 cm measurement being an outlier and the average around 21 - 22 cm (8¼ - 8⅝ in) which falls into Mark Elbroch’s (2019) parameters for a walking gait. The trail looked pretty relaxed, moving in relatively long straight lines exploring here and there. I have read that the Opossum hunts by wandering and sniffing the air, in effort to catch the scent of something to eat. I wonder if scent is the dominant sense of an Opossum?

I only really started taking photos and proper measurements when I came across something which I had never seen before; apparent Opossum feeding sign!

Beside a row of Cedars at the base of a small tuft of grasses and forbs, there was a small slightly conical dig into the snow which went down to the gravelly soil. The dig was about 4 cm below the grass, but didn’t appear to get into the soil. Atop the snow at the edge of the dig there were fragments of a Brown-lipped Garden Snail (Cepaea nemoralis) shell.

This is the first time I had seen any sort of possible feeding sign from an Opossum before and I was stoked. While only one of my books mentions land snails as elements of an Opossum diet, all of the other books name the Opossum as a generalist who will eat anything they can find, especially in the Winter when other foods may be less abundant, and while they may be classified as omnivores, Opossums tend to eat more animal matter than plants or fungi. With 50 teeth an Opossum has more than any other land mammal on Turtle Island/North America. With 18 incisors and a high sagittal crest, an Opossum is prepared to bite chunks off anything they encounter and chew the heck out of it. Insects such as crickets, grasshoppers, beetles, ants, carrion (cottontails, other Opossums, cats, squirrels, Raccoons, skunks, moles, mice, shrews as well as reptiles and their eggs, including poisonous snakes, amphibians, birds and their eggs, land snails, crayfish, earthworms. Some sources say they will consume chickens, but some say they pose no threat. As for plant food, Opossums consume Pokeweed berries, Mulberry, Hackberry, Greenbrier, Groundcherries, grapes, Blackberries, Apples, Pawpaws, Hawthorn berries. Fungi and garbage are also consumed. They just about anything that is available on the landscape, kind of like humans (Homo sapiens) and Coyotes (Canis latrans), which is likely why the Opossum is a resilient species which is consistently spreading their range year after year.

I picked up the snail shell remnants to inspect them and photograph them. I have always wondered if when we find broken snail shells if we can determine who the predator was by the size or shape of the remaining fragments? Sometimes it seems like I guess at the predator based on where I find them, say, in a pile at the base of a tree, or on an elevated area like a stump, but no luck yet based on shape or size of the fragments I find.

When picking up the shell fragments I also smelled them, and that was insightful. The pieces smelled like the musk from an Eastern Garter Snake (Thamnophis sirtalis sirtalis)! This was strange. I wondered if this was the smell of the Opossum’s breath or if the insides of a snail smell similar to the musk of a snake? Do Opossums have some sort of secretions from an anal gland? More I’ll have to look into in the future. Also in the future, there are a couple times during the year when a lot of snails are crushed on the trails. The kids I work with put in a lot of effort to move them, but inevitably some do get crushed. I’ll have to stop and smell their remains to check to see if there is naturally emitting odour when the snails die which I may have never noticed before.

I dropped the fragments and kept on the trail. I made to follow deeper into the Cedar woods when another trail cut across the Opossum. It seemed like they were out and about at the same time of night. When I looked quickly I recognized it as a smaller squirrel of some kind, likely a Red Squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus), who are very common in the area. I bent low to check out the track pattern as it looked a bit tight for a bound, and then noticed that the trail width was a bit smaller as well. Not only that but the metatarsal pads on the hind feet seems more of a C shape than the “rocket ship shape” I am more familiar with in the Red Squirrel.

I measured the trail width for the first bound I came across and it came out to 6.5 cm (2½ in) wide. This was pretty damn narrow for a Red Squirrel and I started to wonder about a Southern Flying Squirrel (Glaucomys volans). In an attempt to confirm the species I measured the width of the track left by the right hind foot: 2 cm (¾ in) wide, a couple of millimeters narrower than the Red Squirrel. The front left foot came in at 1.2 cm (½ in) wide, also fitting the Southern Flying Squirrel and half the width for a front track of the Red Squirrel. The track patterns in the trail showed a mixed gait of hops and bounds, also in league with a Southern Flying Squirrel and unlikely for a Red. I also checked the measurements and morphological features of the Eastern Chipmunk (Tamias striatus) just in case as it was a slightly warmer day and the chipmunk may have awakened from torpor, but the morphology and hopping patterns do not fit with a chipmunk, though the measurements do. I do remember the group length of the bounds overlapping with Red Squirrels but I never took a measurement.

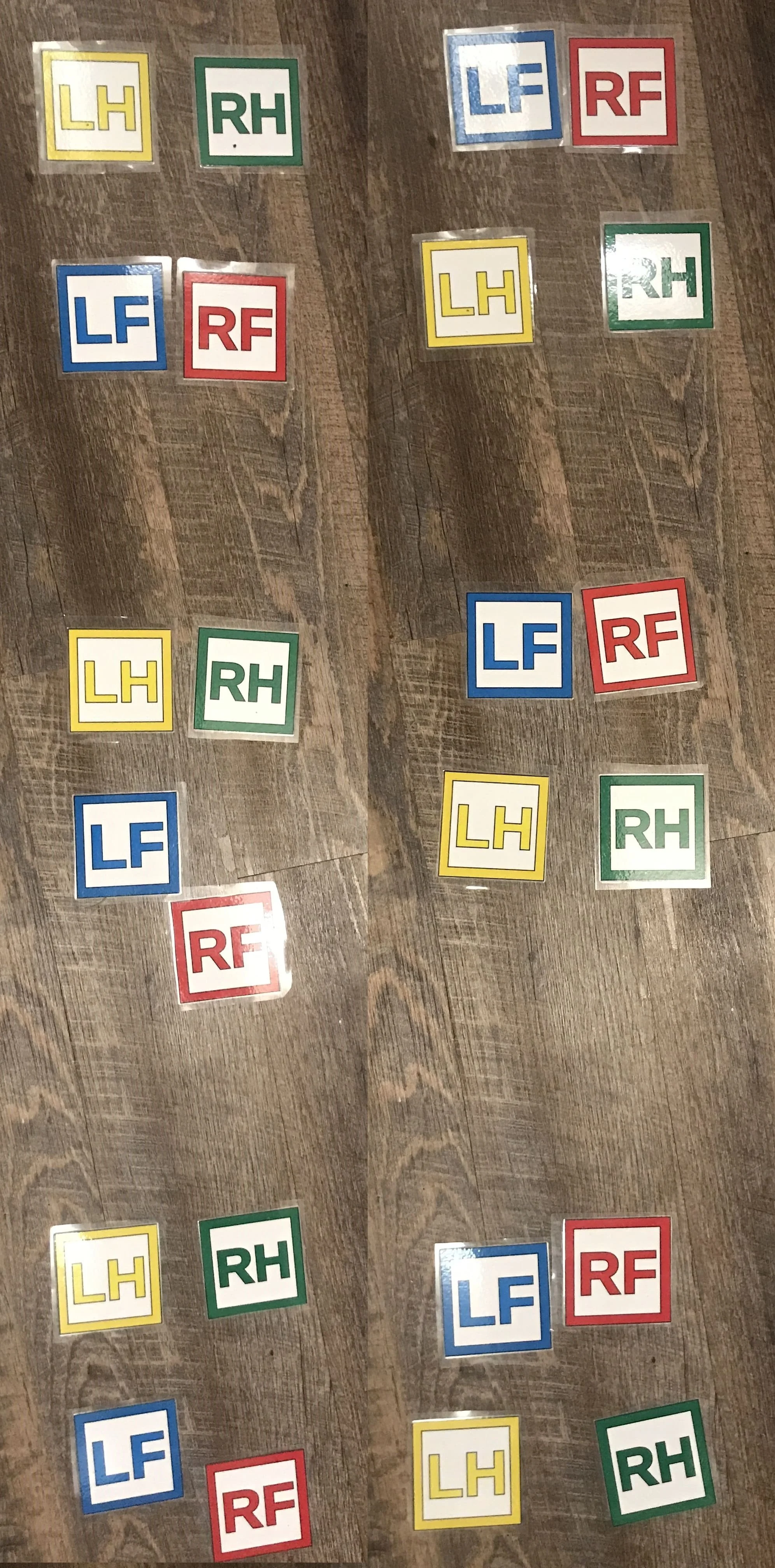

Bound on the left, with a hop on the right

Now might be a good place to describe the difference between a hop and bound when looking at the track patterns. According to Mammal Tracks and Sign by Mark Elbroch, hops and bounds are similar in that the hind feet take off at the same time or relatively so and then land at the same time as well. To differentiate them, in a hop the front feet land ahead of the hinds, while in a bound, the hind feet land parallel to each other ahead of the fronts. I have included an image on the right to help describe this. Many animals can do both of these gaits, but some of them are a preferred baseline gait, their routine regular locomotive movement, like a human walking. For an Southern Flying Squirrel their baseline is both hops and bounds. For a Red Squirrel, their baseline is pretty much just a bound. By noticing the track patterns and looking at which feet land where, we can start to build a multi-factor proofs of who made the trail in question. Based on the track patterns I saw, the trail width of those track patterns and the measurements of the front and hind feet, I say that the trail was made by a Southern Flying Squirrel. I have found many signs of Southern Flying Squirrels in the area over the past few years, including scat, tracks, a nest hole in a tree and even finding a live one trapped in a bird feeder (though I thought it was a Red Squirrel at first). It is always pretty exciting to find signs of the animals we don’t often see, but can know they are present in our environments by finding the signs and traces they leave behind.

When I decided to stop trailing the Southern Flying Squirrel and head back to the Opossum trail I made my way towards and old White Pine (Pinus strobus) I knew in that particular stretch of forest. I knew this tree because I used to come by often with my students and place a nut or acorn in a small hole about 180 cm (~ 6 ft) high on the trunk. This hole is a bit smaller than the holes I have found in other trees with flying squirrels occupying them, but I have always assumed someone was inside as the rim of the hole often appeared to have fresh chew marks. Mark Elbroch writes that squirrels often chew around the rim of the holes they occupy for a couple of possible reasons. It could be that this chewing inhibits the tree from lobeing over and closing the hole or the chews could be indicative of scent making behaviour. I wonder if it could be both? Instead of 123 Pine tree lane, a squirrel marks the tree with their scent so other squirrels who come to investigate the hole knows it is occupied. When I walked by this time, something caught my eye.

When I see this I get stoked. What I believe is happening here is that an animal has made their way inside the tree and as the animal breaths, their breath escapes the tree through the hole. The moisture in their breath creates condensation around the rim of the hole which then freezes and crystalizes, creating both a beautiful jeweled doorway, but also a tell-tale sign of cold weather occupation. If there is an animal inside, I would wager it could be a couple of Southern Flying Squirrels. I want to reiterate that this is what I believe to be happening. I am not sure. I have been wondering if trees release moisture in Winter to minimize the chances of ice forming in their cells, and if this water released shows up as these frost crown circling the cavity holes. Regardless of what is making these, they are a lovely sight!

I got back on the Opossum trail and followed them over and through the fallen crown of a Paper Birch (Betula papyrifera), up to and over a couple of small spring fed creeks, and through a wetland of Phragmites australis. As I wandered through the Phragmites I realized I had walked a very similar path in this same wetland years before while trailing a Striped Skunk (Mephitis mephitis). I remembered the skunk had made their way to the other side of the wet area, up to a large White Cedar and down into a den, which when I checked, had smelled as if occupied. This time, as I made my way around the wetland I decided to avoid crawling through a thickety patch where the Opossum was headed and instead try and cut the trail and just make my way towards the cedar and see if the Opossum also had gone to check out the old hole. Turns out I was correct in my guess, and the Opossum trail went up the small hill to the base of the cedar, led right into the hole and then back out again! I was stoked. It’s nice when you can recall landscape features from years back and the trails which the animals took around that landscape to help figure out where the animals in the present will likely go. Intimacy with place pays off.

I kept on the Opossum trail, hugging the ridge of the low hill above the wetland when I came across something I had never seen before, something which made me shout in glee and punch the air. Know what it was? Of course you guessed it! Opossum scat.

The total length of the scat came in at 12.2 cm (~ 4¾ in), with the four pieces coming in at 36 mm, 31 mm, 25 mm, 30mm. I believe that the overall length would have been different if the the scat was all in one piece rather than four pieces. Due to my measuring from furthest point to the furthest point, and depending on the angle of attachment, two adjacent pieces may have fit at an angle with some overlap which may result in a measurement which is slightly longer than what it might have been, again, if the whole deposit was all attached. The diameters came in between 15 - 20 mm (⅝ - ¾ in) for a midrange of about 17.5 mm. These numbers are close to the numbers I know of in the books with a bit of wiggle room due to the above uncertainty when it comes to total length. Do I have any doubt that this scat was from the Opossum? Not really. It was deposited right on the trail, with only the Opossum tracks around. Dorcas Miller (2022) describes Opossum scat as looking a little like domestic Dog (Canis lupus familiaris) scat in consistency and shape but with a pointed end. She also notes that they are often segmented and longer scats, such as this one, will break into pieces. Many authors, including Miller and Elbroch, state that Opossum scat is dropped at random and not placed in latrines or on high spots like a Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes) may.

I decided to collect this scat and bring it to a stable surface so I could break it down and try and sort out what the Opossum had been eating.

One of the first things I noted as I broke apart the scat was that it smelled bad. It wasn’t too powerful, but it was bad when I leaned in and tried again to better name the details of the smell. I wasn’t able to really draw out what it was that made it bad, but it was bad. Second thing I noticed was that the scat was full of hair, likely from the Opossum grooming themselves. This grooming behaviour has been noted in a few papers I have read on Opossums. I can imagine them licking themselves and consuming any fleas or dirt that has attached to them. You might be wondering about ticks in their scat as Opossums are supposed fantastic tick consumers, but this isn’t really that true. There are many articles (here’s a good one) and a paper (written by that same author) which detail where this idea may have come from and why it doesn’t really make sense. There was no clear sign of invertebrates in the scat I was poking through, but I can also say that there wasn’t clear anything in the scat aside from hair, some sort of fruit skin which may have come from a Rosehip (Rosa sp.) and some mineral matter, small pebbles which were likely eaten inadvertently when feeding on something on the ground. There were also Cedar leaves in the scat, which tells me again they were likely eating something directly off the ground.

When I was finished looking at the scat I brushed it to the ground and wondered at how long it would take to break down in the Winter weather? I wondered if the smell would attract any other animals and who would come and leave more tracks? I wondered at where the Opossum was at that moment and if they were warm enough, or had enough to eat to feel comfortable? I ended up speaking some gratitude aloud for the Opossum, the Southern Flying Squirrel and the whole forest for allowing me to come in and see a little more of the world. I ended up walking back to the car and went home to my warm home, more than full of food, to begin the research which helped inform this post.

Big thanks again to the Opossum and to the lands they wander. I am grateful.

To learn more :

Ep. 155 : Lisa Walsh and Contemporary Range Expansion of the Virginia Opossum

What is a Hemipenis? - another blog post concerning Opossum reproductive organs

Mammal Tracks and Sign by Mark Elbroch and Casey McFarland. Stackpole Books, 2019.

The Wild Mammals of Missouri 3rd Ed. by Charles W. Shwartz and Elizabeth R. Shwartz. University of Missouri Press, 2016.

Scat Finder by Dorcas Miller. Nature Study Guild Publishers, 2022.