Two More Coracoids

Back in March I wrote a post about two coracoid bones I found. As a quick and dirty reminder, coracoids are the largest bone in the shoulder joint of birds which function as a stabilizing column resisting longitudinal compression of the chest cavity by the pectoral muscles when the wings push down. They also protect the lungs from being crushed by the sternum every upstroke of the wings. You can learn more at the link above.

The two I wrote about previously were from two different species, Canada Goose (Branta canadensis) and Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo). Since then I have come across a couple more, one of which I found while looking at the remains of a bird which consisted of feathers and bones, and the other which was just bones. I want to dig in a little bit more below.

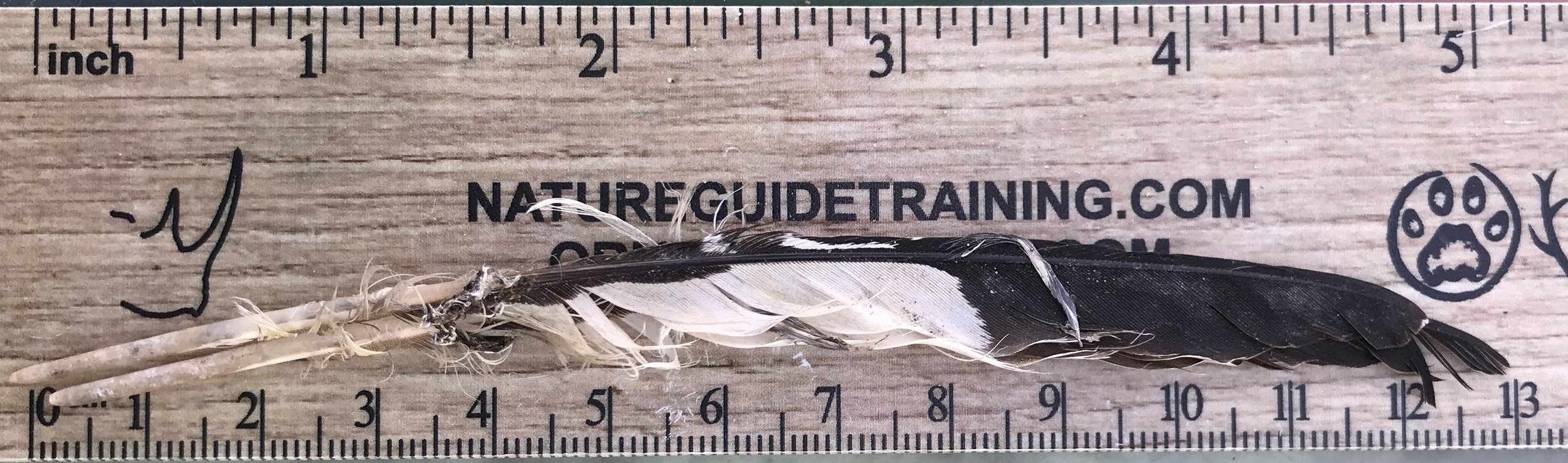

I was meeting my students at a local trailhead and I went out along the river to scout for tracks before they arrived. As I walked back up to the road from the river bank I came across this carcass. My first thought was that the feathers didn’t look like a duck or goose, or any other common birds I might see in the adjacent forest. I figured it might be Belted Kingfisher (Megaceryle alcyon) based on the size and proximity to the river. I remember seeing their feathers before and being confused with a possible woodpecker. The primary feathers came in around 128 mm (~5 in) long. I ended up checking the Feather Atlas website when I got home to be sure and according to both the Feather Atlas and Bird Feathers by David Scott and Casey McFarland (2010), the measurement for the primary feather I measured was just perfect for a Belted Kingfisher. I assume the bird got hit by a car when they were trying to cross over the bridge and landed beside the road.

I noted the coracoid bone as I was checking out the feathers and took some measurements of the coracoid as well. It came in at 31 mm (1¼ in) long.

Measuring the primaries

Posterior view of coracoid from the right side of a Belted Kingfisher

Anterior view of coracoid from the right side of a Belted Kingfisher

Belted Kingfisher coracoid from Avian Osteology by B. Miles Gilbert, Larry D. Martin, Howard G. Savage.

The procoracoid process (which translates to “before, or, front of coracoid sticky-outty-bit”) seems rather sharp, and the sternal process seems less of a slanted strip along the bottom which I saw on the Canada Goose

When I referenced the book Avian Osteology by Gilbert, Martin, Savage, (1996) it was a bit higher than the measurement they offered next to the diagram, but fit for the range they offered (28-31 mm). It was also a great match for the look of the coracoid from the right side of the body. The coracoid was on the larger side, and I actually had this same issue when measuring the Canada Goose compared to Avian Osteology and I wonder if it is a case of Bergmann’s Rule which states that larger individuals of a species are found in colder environments, while individuals in warmer regions tend to be smaller. Could the Canada Geese and Belted Kingfisher in my region of Southern Ontario be larger than individual birds where ever the authors of the book recorded their measurements? Could be. Whatever the case, I am grateful to have that i.d. confirmed.

Fitting the coracoid to the sternum

A couple of days ago I was out for a walk with a friend along the Speed River in Guelph. We were on the SouthWest corner of town underneath the Hanlon Parkway Overpass when they spotted looked up under the embankment under the bridge and saw the messy feathers of a dead bird. I immediately scrambled up the slope and took a look. My first thought, without too much inspection, was that this corpse was from a Rock Dove or Pigeon (Columba livia) as we were under a bridge and the Rock Doves appreciate that particular environment. Perhaps it is reminiscent of their ancestral environments along steep cliffs, crags, and crevices in those rock walls. But as I looked closer at the body of the dead bird I noticed that the shape of the sternum wasn't the same as a Rock Dove and that the feet appeared webbed, though they were all shriveled and chewed. I took some photos in hopes of figuring out the i.d. when I got home, but really, with my limited resources, I was not making much headway.

Based on the wing size, the mostly black primaries, and shorter white secondaries with the speckling fading to black along the rachis, I was guessing this was a female or juvenile Bufflehead (Bucephala albeola), but I really wasn’t certain. The primaries I looked at were still attached to the wing and it was difficult to get an accurate measurement.

Enter instagram and the biologists who have helped me learn more about this dead bird.

I posted a similar series of photos as those on the right and asked for more information. A couple of folks chimed in to suggest Common Goldeneye (Bucephala clangula), a related member of the same genus as the Bufflehead, but a bit larger and more common than the Bufflehead in the area where I found the corpse. I decided that with all of this uncertainty, it would serve me to head back to the body and collect the coracoids, the sternum and a couple of primaries to help get a better i.d.

I did just that. I went back six days later to collect the bones, the feathers and take more photos. Luckily the bird was pretty much mummified and it didn’t take much to find the coracoids. I also pulled the sternum and furcula (wishbone) to see if those would help with the identity when I got home. Lastly, I sang a song of gratitude that I like to sing over dead animals, or plants which I harvest or take from. It’s a small way to acknowledge that I am taking and that the animals and plants are sharing their bodies with me so I can better learn about them, and teach about them in a better way.

I am still learning about how to be more reciprocal and have a long way to go, but I think these songs mean a lot and are a good start.

Measuring the primaries

When I got home, I scrubbed the bones and took some more photos so I could better see the details when comparing with the books. I also checked the books to see about the length of a primary on a Common Goldeneye. According to the Bird Feathers book, primaries for a Common Goldeneye range between 14-16.5 cm. The ones I measured came in at 16.1 cm. The high end of a primary for a Bufflehead is 13.3 cm. The ones I found were larger than would be found on a Bufflehead. I then took a look at the coracoids.

Anterior view

Posterior view

The coracoids measured about 61 mm for the greatest length (GL), 58 mm for the length on the medial side (Lm), 23 mm for the basal breadth (Bb) and 18 mm for the breadth of the articular facet (Bf). These coracoids came in larger than the measurements for a Bufflehead according to Avian Osteology (1996) whose range came in at 31-41 mm for GL and 13-15 mm for breadth. For a Goldeneye the GL is 47-56 mm, and the breadth is 16-22 mm, which is pretty close. Again could Bergmann’s Rule explain the difference?

For a little extra certainty in relation to the morphology of the bone, the shape and size and general appearance, I checked out a few of the images on the Idaho Virtual Museum which I found incredibly helpful. How nice to have these databases online for everyone to use and learn from! Librarians and archivists doing awesome work these days.

So, friends have been asking if I have come up with any definitive answer to whose corpse I found and to be honest the Common Goldeneye is the closest I think I can sort out. I still have some questions though. The neck appeared to be large and white on the carcass, larger than I see in images of the Goldeneyes, but is it just that I have never held one before or seen them up close? When I hold the carcass the white may appear larger than when I see a Goldeneye in the river. I’ll have to pay more attention in the future.

Another question is about the black speckling on the white feathers in the middle of the wing. When I look at photos of Common Goldeneye feathers it seems like they aren’t all the same patterning on each individual, there appears to be slight variation. I appreciate this a lot as there is a bit more possibility within the patterning I found to match with different specimens from a variety of sources. This was a hang up until I started checking out the amazing collections at Featherbase.info .

Lastly, a question which isn’t related to i.d. of the bird. I would love to know who was eating the carcass? There was Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes) scat beside the carcass, and also Raccoon (Procyon lotor) tracks near by. When I first saw the body, laying on it’s back, wings spread with the chest cavity torn into, I thought it may have been a Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinis) who had taken the bird and brought them under the bridge, but I don’t know if feeding under cover is a common practice for Peregrines.

I am grateful for curiosity and adventure in learning here. I have heard that Tom Brown Jr. used to say something like “put the quest back in question, the search back in research,” and I feel like this is what tracking is all about.

A final note here. While writing this entry I had to double check that I was measuring the coracoids correctly and reminding myself of the terminology of the coracoid. I want to include the measuring techniques here so I can practice remembering and in case I ever do forget, I can just check back here.

First, measure the greatest length (GL) of the coracoid. The GL is determined by determining the two most opposite points and measuring from there. It’s not about trying to find the middle of the base or from a specific location on the bone, but more so just figuring out the greatest length that the bone can be measured and using that number.

Second I measure the length of the medial side (Lm). This requires a bit more precision. First you’ve got to figure out which is the side of the coracoid which would be facing towards the midline of the body of the bird. This is the medial side (medial just means “towards the middle”). Next find the bottom inside “corner” of the bone. This is called the “internal distal angle” (located on the second image with a red asterisk). Measure from the point where the asterisk is, again, the internal distal angle, all the way up to the top of the bone. This measurement is your Lm.

Basal breadth (Bb) is a bit simpler. Just measure the distance between widest points of the bone at the base. That’s it.

For the last one, the breadth of the articular facet (Bf), you’ve got to locate the shallow groove where the bottom of the coracoid would articulate (meet or join) with the sternum. This is called the articular facet or the sternal facet (I used the phrase sternal facet in my previous post on coracoids). Measure the length of this facet. What’s a facet? A facet is the smooth area where two bones come together, often bordered by ridges or protrusions which allow the surfaces to fit together snugly without shifting or slipping beyond the functional limits of the joint.

All in all I am so grateful for Common Goldeneye for inspiring me to learn so much more about their anatomy. I am going to be going to do a bit more in depth research on their lifeways and habits in hopes I will become more informed about who they are as a species so I can become a better neighbour. That’s the goal of all of this really; to learn to be, to do and to act better in the relationships I am in, with both the other-than-human and the human.

I am also incredibly grateful for the help of all the people who have been doing the work of figuring out whose bones and feathers belong to who. The researchers, the authors, the hunters, and the institutions who have put so much of this information online which enables me to learn with such incredible detail. I am truly indebted to these folks and hope I can help transform their labour into knowledge to be a better tracker, teacher, and human.

To learn more:

My first write up on coracoid bones : Two Coracoid Bones

The Feather Atlas online feather database

Featherbase.info - another online feather database

Bird Feathers by David Scott and Casey McFarland. Stackpole Books, 2010.

Avian Osteology by B. Miles Filbert, Carry D. Martin, Howard G. Savage. Missouri Archaeological Society, Inc., 1996.

Idaho Virtual Museum collection of Common Goldeneye bones