Tracking journal 2021.10.09 pt. 1

Very shortly after we started out from the parking lot, I noticed the pale long form of what I first thought was a drowned Earthworm in a puddle on the gravel. I walked up and immediately recognized the scales as the underside (ventral) of a snake, but which snake? As I bent down to pick the snake out of the water I noticed they were very small. This narrowed it down a little in my mind and then confirmed as soon as I flipped the snake over.

It was a DeKay’s Brownsnake (Storeria dekayi), one of the more common snakes in our area. I recognize this snake by the grey line down the middle of the back (dorsal) side with brown spots running down the length of the short body. As I held the snake in my hand and folks came in to check them out we wondered at what the snake was doing in the puddle in the first place? Had the snake slipped in while trying to cross the trail then couldn’t get out? Were they in pursuit of a worm or slug to eat? Had it just rained too suddenly and it was too cold for the snake to move quickly and get away from the puddle? The dark blemishes on the on dorsal side just past midway down the body; were those from a predators teeth? Was the snake dragged into the puddle? I really didn’t have any clue as to why and really since it had rained a bunch over night any sorts of tracks would washed away, especially from a smaller animal who would be preying on this little snake. I am grateful we had the chance to hang out with this beautiful creature and get to learn from seeing them so close. Thanks, Brownsnake!

We moved off of the trail and into predominantly Eastern White Cedar (Thuja occidentalis) woods closer to the river to see what we could find under cover of trees amidst the Cedar leaf litter. We got into it really quickly. On my way back from a private tree, I noticed some small white mushrooms with a darker brown spot in the middle of the cap. I knew these mushrooms from trying to identify them over the past few weeks with folks from work. I believe they were in the the genus Lepiota, but regardless of all the research I have done, I can’t seem to figure them out down to the species.

Danielle was carrying the book “Mushrooms of Ontario and Eastern Canada” by George Barron (Partners Publishers) and her suggestion, according to the book could be Lepiota cristata, which I agreed with at first because I came to the same conclusion in past research, but as I write this up and research more, I am doubtful. L. cristata is supposed to grow in grassy areas according to many books and this was in a Cedar forest. I did find one refererence, in Roger Phillips book “Mushrooms and Other Fungi of North America” (Firefly) that L. cristata grows “scattered or in groups on the ground under shrubs and trees, especially Spruce, Redwood, or Cypress, and on lawns.” In my research I have also come across claims of L. cristata being edible, poisonous, suspect, and not edible - possibly poisonous. For now, I think I am going to just admire the abundance of this mushroom without trying to eat them. Really, most things in this world aren’t for me, or humans, but serve their own ecosystems in their own particular ways, and I don’t need to go around wondering if I can stick everything in my mouth.

While checking out the Lepiota, someone mentioned that they had found something they thought I might like to see. I went over and looked around them and saw a mound of mud emerging from the soil. The mound looked like it had been made from many smaller pieces of mud, resembling stacked balls, but someone faded looking, though the mound did not seem as if it had been there for a while, but broke apart as if it was newly mounded. It was light, almost fluffy mud, definitely not compressed.

I had been on the look out for possible Crayfish chimneys over the past few days since I had been shown one on the previous Wednesday by a student of mine. This location where we were tracking was pretty close to where I work and it would make sense to find a Crayfish chimney in this forest, but I think, judging from overall size and form of the mound, that this was not the work of a Crayfish, but perhaps an Earthworm.

Crayfish chimneys look like chimneys. Crayfish construct these chimneys by depositing small balls of mud in a ring around the exit of the burrow. They continue to ring more balls of mud on top of the other rings until a turret shaped chimney develops. They are taller than this mound was and have a central hole that runs from the top of the top of the chimney down to the burrow below the ground. This mound did not have a central hole down the middle, and did not appear to have a Crayfish sized burrow exit when I removed the muddy mound from atop the surrounding soil. What I did see, possibly, hopefully not projecting too much here, so maybe I could frame it like… What I think I saw under the muddy mound was a small exit hole about the diameter of an Earthworm, maybe a couple of millimeters but not too much more. I shared what I thought and then pulled out “Tracks and Sign of Insects and Other Invertebrates” by Carley Eiseman and Noah Charney and read a little more about the Crayfish chimneys. They write :

These turrets may not have a function beyond being safe, convenient places to deposit mud removed from the burrows. The burrow systems allow crayfish [sic] living in shallow, stagnant water to seek refuge in the cleaner, cooler water below. In floodplans and other places with high water tables, chimneys can be found far from the nearest stream. Crayfish construct their chimneys at night by bringing up balls of mud and depositing them around the opening, resulting in a lumpy appearance…

The entrance is usually left open but may eventually be plugged with mud. Old burrows are used by hibernating or estivating amphibians, reptiles, and fish, and may be important refuges for other invertebrates when ponds dry up.

For all the Crayfish in our region, it is amazing that we don’t know more about this cool phenomena. I hope to find more chimneys in the future.

Fungi has been a real focus for me recently. Even though I have been out everyday looking for different fungi, we saw so many varieties and species that I did not know or recognize. I am very grateful for the knowledge of all the folks there that day. I have learned a lot from our discussions and jokes and questions. I appreciate having a crew to wander and wonder with.

Near to where the Earthworm mounds we found a Willow (Salix spp., likely S. fragilis) branch on the ground which had a bracket fungi with strange looking pores on the “fertile surface”.

I had never seen pores like this before, and didn’t know the words to even describe them, until Matt said that they might be called “maze gills”. The pores did look like a maze, and I could imagine a little insect getting lost amidst trying to find their way through. The fungi was a polypore, without gills in the conventional sense, and it could also be described as a shelf fungi as it was growing like a shelf coming out of the dead Willow branch. A couple of folks were throwing around some possible i.d.’s but it seemed like some of those i.d.’s might have been dependent on the branch being from a conifer. I could see that there were Willow leaves all around and a big Willow by Torrance Creek, the little tributary beside us and it seemed like this was the only possibility. Later when I got home, the Willow branch became an important clue in the identification of the polypore, maybe not as important as the pattern on the underside of the fungi, but still necessary.

After reviewing some books and websites, the final solid confirmation came from the book “Polypores and Similar Fungi of Eastern and Central North America” by Alan E. Bessette, Dianna G. Smith, and Arleen R. Bessette. I used the key at the beginning of the book, and even though I got it wrong a couple of times, I think the fungi was the Thin-maze Flat Polypore (Daedaleopsis confragosa). They describe the upper surface of the fungi as

“coarsely wrinkled, rough and scaly at first, becoming finely velvety to nearly smooth in age, with concentric zones, yellow-brown to reddish brown or greyish brown; margin thin and wavy, white when actively growing. [emphasis mine]”

Now this is a small detail, the “white when actively growing” part, but for me it teaches me more than just the i.d. It teaches me some depth around the species, gives more meaning to the details and helps me understand the fungi as a life form beyond just a stationary body in space. The fungi was actively growing! It was alive! Again, this might be understood and expected, even a bit of a “yeah, so what?” moment, but in a culture that was and sometimes still is actively challenging the animated nature of the more-than-human, this small note signaled recognition, and made space for this form of life to be more than an empty accessory on the forest floor. I truly want to see more books that detail, acknowledge, and maybe even celebrate the livingness and communities of the more-than-human. I know a lot do already, but I would love to see more (like this one).

Everyone continued to check out the Thin-maze Flat Polypore and trying to tease out details and see a little more, Steffanie S. pointed out a Snail shell she had found. This caught my eye. I am used to seeing Brown-lipped, or Grove Snails (Cepaea nemoralis) and White-lipped, or Garden Snails (Cepaea hortensis) but this Snail was a little different.

My research is leading to me in a lot of directions, but based on the size and form (heliciform) of the shell, along with the alternating reddish brown blotches, leads me to think this is the shell of a Flamed Tigersnail (Anguispira alternata).

I have been learning that all of the snails in the genus Anguispira are woodland snails, and are endemic to North America, meaning that North America is the only native range Anguispira snails. They would only be found in other parts of the world due to transportation by humans. The species Steffanie found, A. alternata, usually climb trees in wet warm weather, especially at night, to feed on fungi and rotting wood. The Flamed Tigersnail (and maybe other species in the genus Anguispira) become dormant in the winter and I read that laboratory populations of A. alternata require exposure to low temperatures before reproduction. Because of that, it might be that warmer winter temperatures due to global warming might threaten more southern populations of A. alternata. I also tried looking up habitat preferences of A. alternata, but it seems not to be too conclusive, though one paper suggests that “[r]ich deciduous forests with abundant leaf litter and downed wood and adequate soil moisture support the largest A. alternata populations, especially on north-facing slopes.” This was not the forest type we were in when we found the shell, but we were on a very gentle north facing incline. I will have to keep an eye out for more Flamed Tigernails in the future and try and keep track of where I am finding them.

As we kept walking we came across some wetter spots in the forest, areas overgrown with Jewelweed (Impatiens capensis) but as I got in close to look for remnants of Jewelweed seed pods I ended up finding a different plant which I really know nothing about.

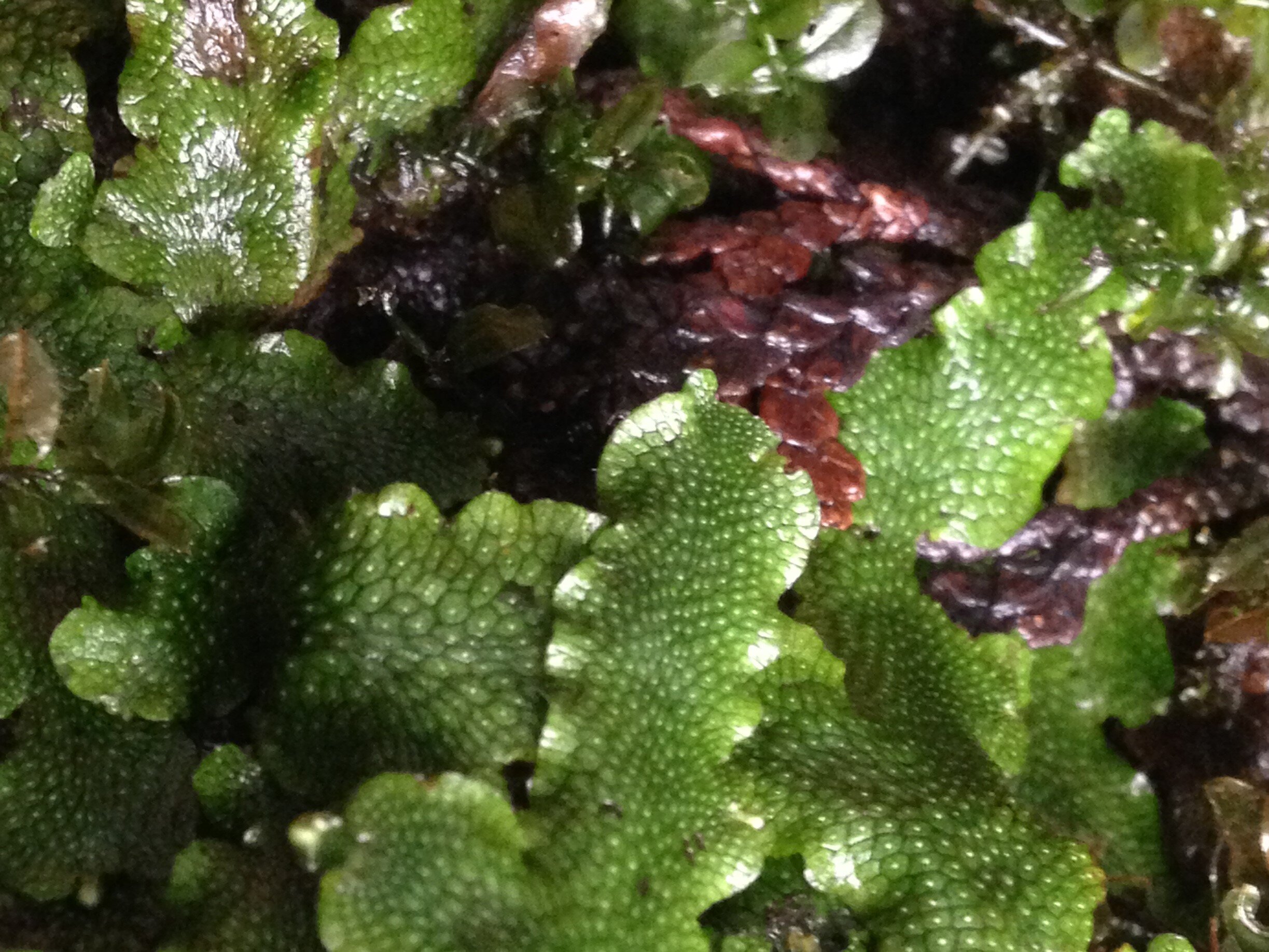

I asked folks if they knew what kind of plant it was and I suggested a Liverwort, but I couldn’t name which Liverwort or why I thought it was a Liverwort. I was doubtful of my naming this plant, but then as Matt came over I asked him if he knew who this plant was and he mentioned, also maybe a little doubtfully, that it may be a Liverwort. This was great validation. Two folks, with no experience, both suggesting a possible Liverwort. We were on the right track.

We noted that the plant was growing in a very moist muddy spot where when I stepped close the mud would suck at my boots and it was pretty difficult to pull my feet out of the muck. I also noted deep grooves (I actually thought they were veins until reminded by someone that they are not vascular plants) in the leaves (actually not leaves). There are some leafy species of Liverworts, but this is a thalloid species, meaning that this type of growth form is undifferentiated into root, stem, or leaf, but instead the form is relatively consistent in the entirety of the plant. Another cool thing I have learned about Liverworts is that as a group they are more ancient than mosses, or Horsetails, or ferns, but because their tissues are so soft, fossilization was difficult. This means that the ancestry is difficult to decipher compared to other life forms with less squishy bits such as trees with lignin, or reptilians with their bones.

This species is likely Conocephalum salebrosum, or Snakewort. The common name likely comes from the scaly looking not-leaves. C. salebrosum looks like another species in the Conocephalum genus, C. conicum but they differ in a couple of ways. First, it seems like C. conicum grows in Eurasia and not here, C. conicum also has fainter not as pronounced grooves, and that the Conocephalum salebrosum, or Snakewort, grows more often on limestone, and other strongly calcareous substrates such as might be found in the Eramosa River Valley, where we were tracking. I think this info about the preference for limestone is pretty cool. I have been talking to folks a bit lately about how plants can teach us to see what is going on below the surface, and this is a perfect example of that. Some plants, like Viper’s Bugloss (Echium vulgare) have a strong affinity with limestone, Common Juniper (Juniperus communis) can be indicative of past land use of intensive pasture as they can only grow with no competition on poor substrates - worn out from grazing animals with little input back into the soil. If Snakewort prefers medium shady, consistently moist or wet conditions (including occasional submergence in water), and either rocky ground or rock surfaces with a thin layer of soil than I can use this knowledge that the plant shares of its habitat and make informed choices - don’t build there, don’t build a fire there, don’t plant a annual vegetable garden there, don’t expect to find more mesic plants around. By learning this plants preferences and the preferences of other plants than we can come to know the land better and understand a greater sense of the ecology of that habitat.

I think I was getting distracted and needed to move a little bit and was making my way up a small incline when I saw what looked like a bone in the Cedar leaf litter. I bent down for a second and picked it up. It was a bone. It was the back right quadrant of a cranium, part of a skull. I looked around more carefully and began finding more pieces of the skull, some mandibles, and a couple of other bones. I called out asking if anyone wants to help do a puzzle with me and we brought all the pieces to a flat surface where we began trying to put it all together.

I thought I knew who the animal was from which this skull was from. I wasn’t 100%, but I felt maybe 75%. As folks were reconstructing the skull I asked some questions and we wondered aloud about the cranium (brain case), and mandibles (lower jaws). We looked at the mandibles and examined the different pieces. Someone noticed how intact and unblemished the teeth were, and one of the teeth hadn’t even erupted from the bone yet which can be interpreted as being from a younger individual. The teeth were also fun to look at to help indicate the dietary habits of the animal. I think many of us also noted the hole which pierced the back of the cranium close to where the foramen magnum was. I wish there had been two holes in the skull so we could have measured the distance between them and cross referenced the distance with the width between local predators in the area to see if we could figure out who had bitten into this animals skull.

Once the puzzle was as complete as it would get considering we did not have all of the pieces, we debriefed who we thought this skull belonged to. The list was something like Muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus), Weasel (Mustela and Neogale spp.), Striped Skunk (Mephitis mephitis), and Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes).

Muskrat (above) was out because of the shape of the premolars. The remaining teeth in either mandible were premolars, teeth which Muskrats do not have. They were also too pointed, where the Muskrats molars are ridged crosswise as opposed to lengthwise (Muskrat teeth look like extra large Vole teeth). Muskrat just didn’t make sense for this one.

Weasel (male Short-tailed Weasel (Mustela erminea) or female Long-tailed Weasel (Neogale frenata) pictured above) skulls are small in our area. Even a larger animal in the Mustelid family, like a locally common Mink (Neogale vison), would have a skull smaller than the one we found. The entire length of the skull would be flatter overall and less bulbous in the braincase. The auditory bullae would be flatter and more square-ish and the coronoid process (sticky-outey hook shape at the back of the mandible) would be more triangular than the mandibles we found. If by some amazing luck they ended up in this region, these same clues would apply for a River Otter (Lontra canadensis) as well. Weasels of all stripes in our area are out!

Striped Skunks (pictured above) are plentiful around here, but this was not a Skunk skull. A Skunk skull would be much too small for the one we found, even if the one we found was likely a young individual. A Skunk’s auditory bullae are small, flattened and are tucked in a little more anterior (towards the front of the skull) than the one we found. The coronoid process is more rounded and less hookish as well. Striped Skunk? Nope.

Red Fox (pictured above) is a tricky one. When I saw the mystery skull I didn’t give it a second thought that it could be a Fox, but when I got home I double checked just to make sure, and I realized that the Red Fox skull and mandibles are more similar to the mystery skull than I had originally assumed. I had mentioned that there were two mental foramina at the anterior of the mystery mandibles, assuming that the Red Fox did not have those, but sure enough they do! I had assumed the coronoid process on the mystery mandibles had more of a hook at the back while Red Fox mandibles are more vertical, but in comparison at home the mystery mandible was just slightly more hooked and this would not be a good field sign for certain i.d. in the future. The size would be a good field sign, though younger individuals may be smaller than usual and may throw someone off. In the end, it is the accumulation of slighter details which would help differentiate the mystery skull and mandibles from Red Fox. The mandibles of the Fox are relatively longer and more slender than the mystery mandible. This is subtle but with more time spent with mandibles you can start to feel it out. Also, the bottom of the mystery mandible curves upwards towards the angular process (another pointy-sticky-outy bit at the back of the mandible) just behind the last molar more so than the Fox mandible would. The cheek teeth, which include the molars and premolar teeth, have multiple cusps on both the Red Fox mandible and the mystery mandible, but the mystery mandible’s cusps are not as high or sharp as the Red Fox. Someone with more knowledge than I do could probably write about more differentiations between the two, but I am going to stop here.

Who do I think the mystery skull and mandibles belong to? I think they are from Procyon lotor, or Raccoon. I have been cleaning a couple of Raccoon skulls recently and I have found multiple Raccoon skulls over the past few years so I have had the chance to look at them up close, a lot. That is the first thing to inform my assumption. When I find something in the woods, and I am unsure of the i.d. I always want to assume it is rare or unusual. I don’t know why I do this, but I recognize that I do and I am trying to train myself to remember that I am more likely to come across common species than rare ones, so assuming a common species first is always a good bet. Second item informing my assumption is that I had found the skeletal remains of a Raccoon in that very forest a few months before, but the skull and mandibles were missing (I had to i.d. the remains by the scapula). My familiarity with the location helps me know who hangs out there, and sometimes, who has died there recently. Thirdly, all the details mentioned in the descriptions above accumulate to discount other species while upholding Raccoon as a remaining possibility. I was 75% sure out there, but after looking at the skulls and mandibles at home I am now 95% sure. Why only 95%? I only have those photos I took to compare with, and I really don’t know where I am still unaware - I don’t know what I don’t know. But for now, 95% is enough to roll with.

What incredible teachers these bones are! What a gift that we can come into the community of the Cedar forest and learn with open minds and hearts, taking in the beauty and diversity of forms of life. What an amazing artifact the skull is to teach us about the life history of an animal. I honestly and really hope someday my skull can be used for teaching, not just in some university setting, but perhaps in the field with students of all sorts. I am grateful for this Raccoon who lost their life and grateful to the forest which left the pieces for us to investigate.

After we pieced together the skull some folks decided that it was time to head out to their cars. It had already been three hours and some had other things they had to get to. We had a quick closing circle of gratitude and those who had to leave did so, while four of us kept going for the rest of the afternoon.

BIG THANKS to Matt for the gift of a field lens. It opens up so much more to be seen.

This is the end of part 1. Part 2 can be found here.

For more info check out some of these links to books and pdfs:

Reptiles and Amphibians of Toronto (pdf)

Mushrooms of Ontario and Eastern Canada by George Barron

Tracks and Sign of Insects and Other Invertebrates by Carley Eiseman and Noah Charney

Species of Ontario Crayfish (pdf)

Identifying Land Snails and Slugs in Canada (pdf)

A Guide for Terrestrial Gastropod Identification (pdf)

First Life on Land : Ontario Beneath Our Feet (about Liverworts in Ontario)