building relationship and intimacy with the land

All about connecting with the land, seeking to inspire resilience, resistance, and reverence for the land.

Located within Thadinadonnih (“the place where they built”) on Treaty 3//Between the Lakes treaty lands, territories of the Mississaugas of the Credit, now known as “Guelph”.

As we get ready for the longest night of the year, it’s also a time to celebrate traditions and set our sights for the new year with the rebirth of the Sun. Making radio for me also holds traditions embedded within the episodes. Every Solstice I dig into the archives and pull out a rebroadcast which was originally aired December 21st, 1985 at 10:30pm on the BBC. And now, for the 8th year in a row, I get to broadcast one of my favorite pieces of radio.

While out tracking in the new snow the other day I came across some relatively small tracks, reminiscent of a Chipmunk. It took a second before I recognized them as Southern Flying Squirrel tracks.

I have been encountering Southern Flying Squirrels in various ways for a few years, including tracks, scat, feeding sign, live sightings, and I even pet one once, but through all of this, I didn’t know much about them. Hence, inspired by my recent tracking outing, I figured I would take some time to get to know the Southern Flying Squirrel a little better. Hopefully we can learn a little more together.

While tracking White-tailed Deer at Mono Cliffs with the Earth Tracks apprenticeship, we saw lots of signs of the rut and the subtle ways deer communicate. We studied three main signs: scrapes, rubs and lick branches. Together, these clues form a multisensory language of scent, sight, and even ultraviolet signals that share details of identity, territory, and mating readiness. These clues along the trail are a real insight into how deer express themselves across the landscape in ways most of us overlook.

I have missed a few of the notable migrations this year; Salamanders, raptors, and until yesterday, the Chinook Salmon. The salmon are a unique one on this list for me though, special in a strange kind of way.

This episode was recorded along the banks of the Credit River, a river which has shaped me deeply and set me on a course I am wading my way through.

I am unfathomably grateful for the salmon and for the river for sharing so much with me and helping to shape this episode.

It isn’t often that I get to see bear scat down here in Guelph, but in Parry Sound, there are many Black Bears, and while visiting the Sound for a trailing workshop, we came across some of their scat.

Even if we don’t get to see the bear, their scat was plenty enough to get me thinking about the plants their consuming, how their digestion works, and how their being themselves impacts and plays with the land they make up and inhabit.

Slowly colonizing the sunlit fields and edges, home to all sorts of creatures both large and small, these towering monuments tell of the abundance of the land. Black Walnuts are amazing allies in healing, mentors in boundaries, relative buffet in mast years, and year round marker of beauty. Who doesn’t want to sing their praises! Maybe by the end of the show, you’ll love them a little more too?

Over the years I have investigated Goldenrod on different levels, from the technical and scientific to the intuitive and relational. Both vantage points have served in getting to know these amazing and powerful plants better. I decided to head out with a makeshift milk crate studio to sit with the Goldenrod, Bumblebees and Crickets and make a show together. I hope this helps shed a warm golden glow on these essential components of the Great Lakes bioregion.

Sisters Alex and Tasha Sawatzky’s knowledge of and growing appreciation for the land they lived on was tangible and real, so how could they tell the stories of the species they were coming to know and love, while also countering the dread of our modern world? They decided to start Minnow, a magazine about ecology, conservation and all sorts of species we share a home with.

I had to do an interview to learn more.

Many of us have cut ourselves off from the natural world by “gating” our senses, only using what is needed to navigate an urbanized, mechanical, constructed and conditioned environment, and we end up isolating ourselves, and leaving the more than human world behind. In times of ecological, political, and climate horror, I wonder at how we can remain connected with the wilder places we love? How do we engage with the land with all of our bodies and minds, working and practicing the sensual gifts we have inherited from millions of years of evolution?

Inspired by a fun workshop I got to host, along with such an amazing history of evolution though incredible cataclysmic epochs, chock full of climate upheaval, I really wanted to learn more about these amazing plants. Many of the Equisetum genera are now extinct yet there are about 9 species in my area, and of the species which persist in the area, I will be focusing mostly on Rough Horsetail.

Grey Treefrogs are my favourite frog species at the moment. They are cute little colour changing, antifreeze laden, Lichen-Spirits who really belt it out when trying to find a date. I have been hearing them pretty much nightly lately, screaming their short trill all over nearly every wetland I encounter as long as it is fairly adjacent to trees. Because of their powerful calls permeating my late night waking life, I have been wanting to take a deeper dive.

Hope you enjoy!

It started with a little hole at the base of an Eastern White Cedar tree, and a couple of seeds. Who had collected and consumed the contents of the seeds? What about the feathers? And the boney remnants of bill?

Join me as I go deep down a Deer Mouse hole.

Eardrum bursting calls of the Spring Peepers are a very welcome sound for me. To borrow a phrase from Kim Stanley Robinson, their “cascading recombinant chaos” preaches a promise of Spring, and it fills me with immense joy. So much so, that when I first heard it this year I dragged my students across the road to listen to the frogs scream their little hearts out. I later went back, twice, to record them. Once on my own, another time with my partner to capture the wailing, and read a little bit about them so as to learn more. That’s all this show is about. Praise for the choir.

I have been excited about Song Sparrows for a while. Theirs was one of the first complex songs I learned to identify, and being such a common neighbour on the landscape it’s hard to go a few days without hearing them, even in Winter, but especially in the Spring.

While out today, I came across a couple Song Sparrow tracks in the silt newly laid down by the receding Eramosa River flood waters and it pricked my interest to dig in a little deeper to this common figure in my life.

I have found sign of three dead White-tailed Deer in the past three weeks. One, killed by Coyotes. Another, hit by a vehicle, found on the side of the highway. And also, I found a White-tailed Deer leg while trailing a Coyote. All of these encounters have been teaching me a lot about the legs of the deer and I wanted to look a little bit deeper into these moments, and to share the stories.

I go on to detail what I have been learning about the legs, especially in the context of the hind legs, about the glands located there. Of course, you can read the blog post, or you can learn a little bit more from listening to the show.

Fishers aren’t known as an urban adapted species. They tend to avoid our built up landscapes and prefer mature forests comprised of old trees with cavities and lots of course woody debris (think of big piles of dead branches and fallen logs). Because of this Fishers avoid our cities… or so we thought.

Sage Raymond is a researcher who studies urban adapted Coyotes in Edmonton. While out checking some trail cams intended to catch Coyotes on the landscape, she happened across a Fisher trail in the snow. Sage realized that this was a very unusual circumstance and wrote a paper about it. Thankfully, she agreed to talk about her findings on the show.

As I mentioned on the previous show about the Lynx trailing trip, I was planning on heading up to Algonquin Park to trail Moose, Algonquin Wolves, Martens, Snowshoe Hare, Flying Squirrels, and whomever else’s trails we may come across. Well, I went and it was great. So good that I wanted to offer a bit of a report back from the trip and tell some stories of what we saw.

This is the 24th year of this trip, and I am so grateful to get to not only be there, but to be helping lead the week. Kid me would be stoked… hell, adult me is still stoked!

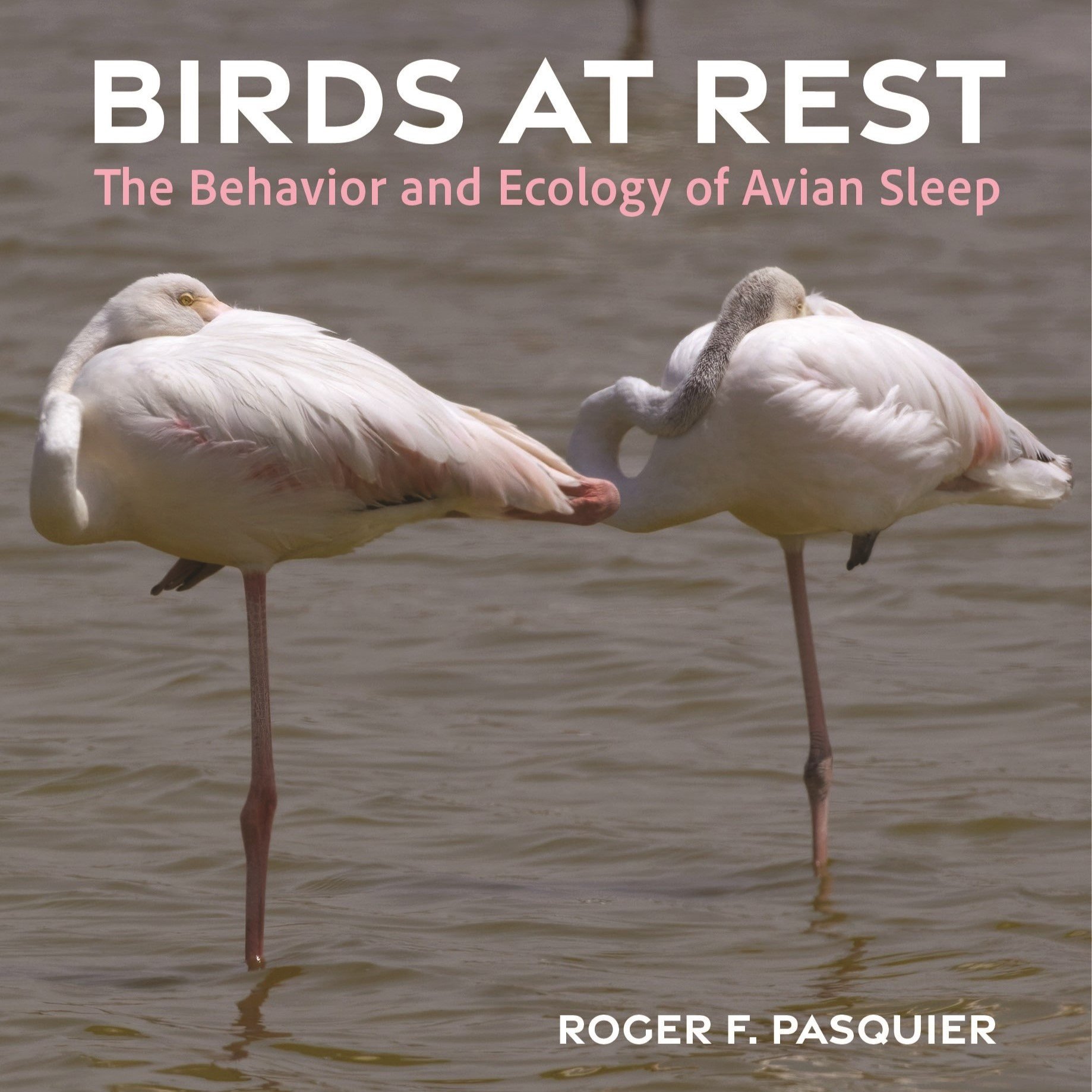

I have had a lot of conversations with biologists and ornithologists over the years, trying to learn about how different animals sleep. Are the functions of sleep in humans similar to similar animals? What about different kinds of animals, like insects, or birds?

Does photoperiod change the amount of time birds sleep? How does the changing climate affect birds at rest? Do birds dream?

Roger Pasquier has taken the time to collect the information from a ton of various studies into avian rest and sleep and consolidated them into a useful and interesting book, and then taken the time to discuss some of this research on the show.

I just got home from an amazing week away trailing Lynx. It was an amazing time and I had a ton of fun. We trailed Lynx for days, as well as get on some trails of other animals. There are so many stories to tell and so much to integrate over the next few weeks, but I wanted to share some highlights of these weeklong tracking expeditions.

I was out for a walk along the Eramosa River in Guelph with a pal on New Years Day, when she lifted a log and showed me some strange white patches along it. I guessed by the appearance of them, being small, white and silken-like, with many around, that they were likely egg cases of some small invertebrate.

White, circular with a thin shallow dome constructed of webbing got me wondering who may have created this? I decided that this find, like a lot of the small wonders of the world would be worth researching a bit and recording a show about.

It is nearing the Winter Solstice once more. Only days to go, and that means with the dark nights growing longer, I am spending a little more time indoors.

This time of year also means the recurring celebrations of the solstice season are upon us again. Story telling, big fires, sharing food and giving gifts are big this time of year. More pertinent to the show though is the rebroadcast of the 1985 radio play by Alison McLeay “Solstice” for the 7th year in a row!

Get yourself a nice warm drink, a cozy blanket, dim the lights and enjoy.

I spent the day out tracking, when I got to thinking about gifts that are the tracks which are left behind without consideration of how the tracker might feel or what we may want out of the experience. I was struck by awe and wonder when I came across the bed and was truly grateful for this gift left behind by the animal that was there so recently.

Blue Triton was formed when two private equity firms bought Nestle Waters Canada with junk bonds and hugely leveraged debt. They continued Nestle’s legacy of bottling water across North American into polluting plastic bottles made from fossil fuels. Blue Triton are now moving out, and may likely try and sell what’s left of the operation in hopes to recoup some of the costs.

This was a huge victory for local water advocates, and I wanted to learn more so I invited Arlene back on the show to give me the scoop on what was happening and how Water Watchers ran such a successful campaign. Lots to learn here.

In the later part of the Summer, I was walking with my friend and colleague Tamara when we came across some scat with Apples in it. I can’t remember what brought it up but she mentioned that she has seen more scats composed mostly of Apple left by Coyotes rather than by Red Fox. This got me wondering.. who eats more Apples, Coyotes or Red Foxes? This question began a weird hook in my mind, and everytime I noticed Apples, Apple based scat, Coyote scat or Red Fox scat, the question would come to mind.

I decided I would go for a walk and try and measure a ton of scats, look for evidence one way or another and see if I could get any closer to an answer. Ended up making the show about this question.

Listening to the land, in a very tangible way, can lead to some pretty special moments. Whether it is Black-capped Chickadees scolding an Eastern Screech Owl, hearing the thunder heralding a powerful storm, or the waves washing up on the beach, the land speaks to us through sound in thousands of ways. We just have to stop and listen.

I brought my recorder with me out to McGregor Point on Naadowewi-gichigami/Lake Huron incase any sounds moved me, and of course, such a big beautiful sea tugged at me in the foggy morning. I had to record.

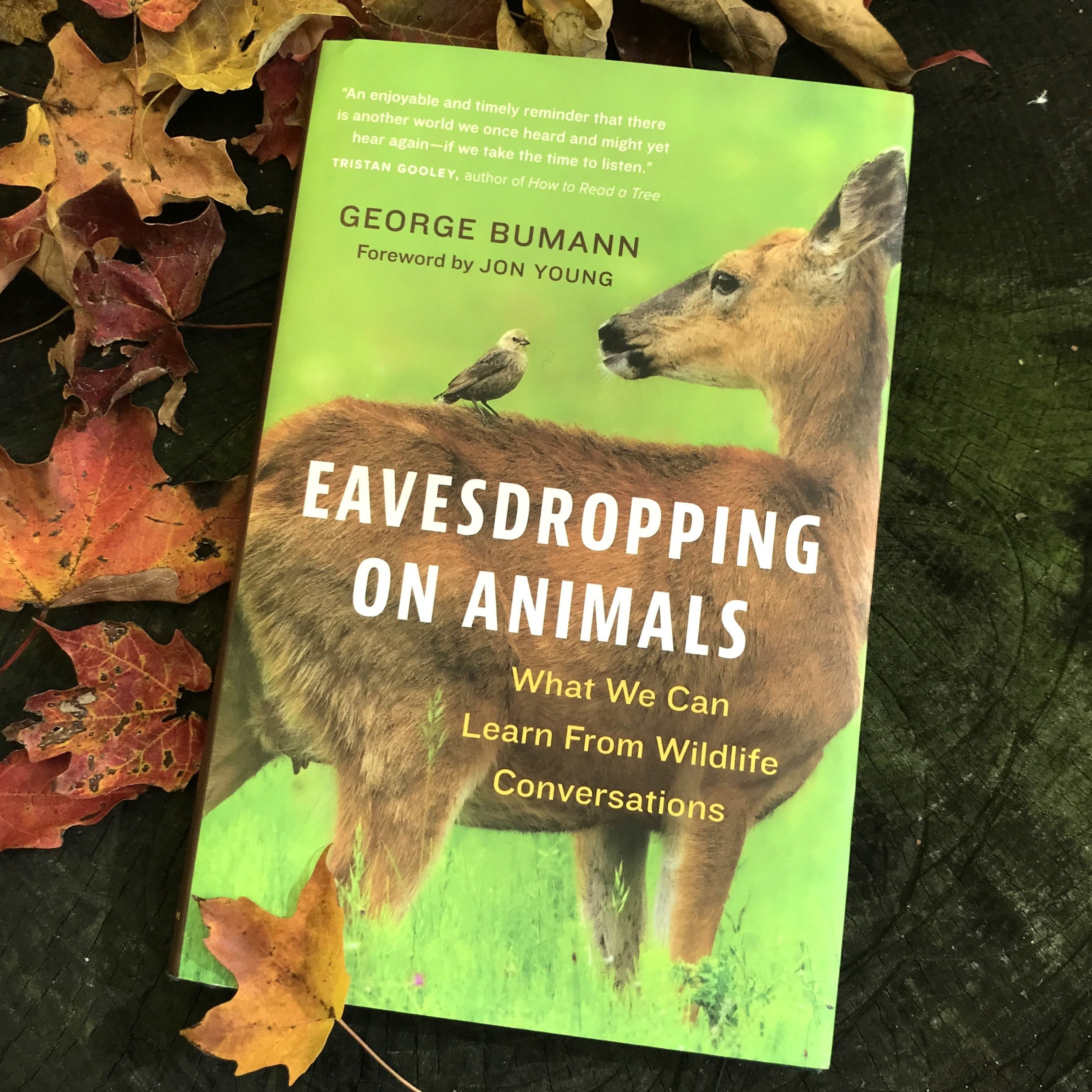

Aside of our human cultural space there is the broad other-than human animal place. A world we exist along with, and yet are still achingly removed from. This wilder edge is always calling out, audibly and silently, with gesture, scent, behaviour and sound. George Bumann has been practicing paying attention to this world in ways that I long to.

As Julie Beeler writes, it wasn’t until 1969 that fungi were taxonomically separated from plants and recognized as inhabiting their own kingdom. There is so much that we do not understand about their taxonomy, their natural history, their functions in their ecosystem, or their medicinal values. With all that we do not know, Julie Beeler’s amazing work, set on paper as the Mushroom Color Atlas draws a clear path towards understanding the possible tones and timbres of colour and shade which we can pull from some of members of this vast kingdom.

While teaching up at the Lodge at Pine Cove this past weekend we came across lots of tracks and sign. But there was one bit of sign that was really annoying me… something I wasn’t sure about. There were mussel shells laying about all along the rivers edge. Along the beach, the rocky cove, and all across the depths of the French River. They had all been opened, most split at the hinge, some cracked, many fragile and crumbling apart when put a bit of pressure on them. Someone had been feeding on these mussels for quite a few years it seemed, and I wanted to, maybe even needed to, figure this mussel mystery out.

For the last couple of years, I have been going to Pawpaw Fest which my friend and neighbour Matt Soltys organizes. Matt Soltys, for those listeners who don’t know yet, is The Urban Orchardist. He teaches me about fruit and nut trees and I help him try and sort out which insects are leaving their sign on the trees.

But back to the point… Pawpaws. Asimina triloba. A fruit with a comeback story. Have you tried one yet? I bet most folks listening have. They are growing more and more, both literally on the land and metaphorically in all the surrounding hype. Is it worth the hype? Matt Soltys seems to think so. He is growing hundreds of them (I had to fact check this statement, and yes, it is true).

I have been spending the start of my time off climbing, going to yoga and plotting tracking trips to new areas within an hour’s drive of Guelph. I am on the search for different landscapes to explore and potentially encounter new environments I don’t normally get to within or on the periphery of the city. For the past couple of days I have been exploring Puslinch Lake Conservation Tract, and it’s an interesting spot.

On Wednesday December 17th, 2025, while out exploring the river ice with my students we came to a bend of the Eramosa River where I knew the ice was thickest. While out on the ice, I came across some interesting tracks. Coyote tracks double registering? Fisher? River Otter?

Here I detail how I came to the conclusion of River Otters.

While tracking White-tailed Deer at Mono Cliffs with the Earth Tracks apprenticeship, we saw lots of signs of the rut and the subtle ways deer communicate. We studied three main signs: scrapes, rubs and lick branches. Together, these clues form a multisensory language of scent, sight, and even ultraviolet signals that share details of identity, territory, and mating readiness. These clues along the trail are a real insight into how deer express themselves across the landscape in ways most of us overlook.

Bebb’s Willow is a species I encounter commonly, but I do not know much about. I can’t even accurately identify them. They have become the subtle whisper of species ID I feel inside me whenever I cannot identify a small wetland shrub that sorta looks like a Willow. I have decided that I will take a closer look.

I went to the beach the other day and I found a bone washed up. The bone struck me right away as looking like it was from a bird. Perhaps I remembered it from a previous bone study or from a skeleton I had observed before. I inspected it quickly, and put it in my pocket to look at a little more later before continuing on my way.

I am very much interested in the edibility of invertebrates. Recognizing that most of the world commonly consumes insects and other inverts, I get to wondering why we in the Northern parts of Turtle Island/North America don’t really consume them.

In light of this wondering I have been setting out to learn as much as I can about which insects I can eat, and how I can learn to prepare them. Below I will be creating an ever expanding list of insects and other inverts I have eaten and how I have prepared them.

While out tracking with the Earth Tracks Widllife Tracking Apprenticeship along a stretch of beach at Lake Huron at Saugeen First Nation we came across the fairly decayed carcass of a medium sized bird...

There was a sudden movement directly under where my foot was about to land. Something large and pale brown jostled about and I quickly called out and stumbled back. It took me half a second to realize that the large pale brown shape that was moving away from me was a White-tailed Deer fawn. Reflecting afterwards, I realized that I didn't know much about fawns, so I had to find out more...

It seems differentiating between Jumping Mice and Voles in my area is a persistent struggle. I have confused them on study calls and most recently on another TCNA Track and Sign evaluation (earning me 99% instead of 100%). With this latest affront to my pride I decided I needed to work through the tracks with more focus and practice seeing the minute differences of these minuscule tracks.

“Which way them critters goin’?”

To this day it can be tricky to tell the direction of travel through deep snow.

For this exploration in determining the direction of travel I’ll use a snowed in Fisher trail we encountered during an Earth Tracks Tracking Apprenticeship outing at Bognor Marsh, near Meaford, Ontario as an example. It was a faint trail, mostly snowed in, but the impressions were visible at the right angles, as long as they hadn’t been blown away in the wind.

I found a White-tailed Deer leg while trailing a Coyote. I ended up taking the leg. Why? Well, I thought it would be a good chance to take the leg home to study it and learn more about deer. This post is about my findings, especially in regards to the glands distributed along a deer’s leg.

Recently, at a TCNA “tracker tuesday” call, there was a challenge proposed: on your next tracking outing, practice following the deer or the rabbits and see if you can find 10 plants which they fed on. For me in my area, the deer would be White-tailed Deer and the rabbits would be Eastern Cottontails. While I have been observing the Cottontails loosely at work with my students, for this tracking outing with the Earth Tracks Wildlife Tracking Apprenticeship, we focused on the White-tails.

I knew who the trail belonged to pretty much right away due to the oscillating midline that ran through the length of the furrowed trough in the snow and the occasional spotting of urine that was sprinkled intermittently along the run. This was the trail of the North American Porcupine, a common fixture in the forests of Dunby rd.

For the past few years I have been tracking the Scout Camp beside where I work. Lately with the students, we trailed an Opossum around the area.

This time I went back alone in hopes of learning more about the Virginia Opossum and see what they were up to. I wasn’t let down.

I have written about coracoids before, but since realizing they are very helpful in the identification process of birds, it has become a bit of an ongoing puzzle now.

This post is about finding two dead birds and using their coracoids to sort out who they were with a little more certainty.

I recognize that these are epic cataclysmic histories, but the stories held in the stones at Old Baldy have brought about a deep sense of peace for me when it seems so lacking in the world right now. Maybe it’s the disconnect of me not being present for the upheaval and torrent of glacial meltwaters and crushing sheets of ice, but doing the research, piecing together clues, and imagining the magnitude does create a profound sense of wonder and awe, a stupefying amazement in the unveiling of a billion years of mystery written on the body of the hill. I deeply appreciate the work and practice of listening to the stones and tracking the beauty of the land.

Another beautiful, exciting and overwhelming trip with the tracking apprenticeship to Saugeen Shores. Bird tracks, invert sign, reptiles, and more met us on the sandy shores of Lake Huron.

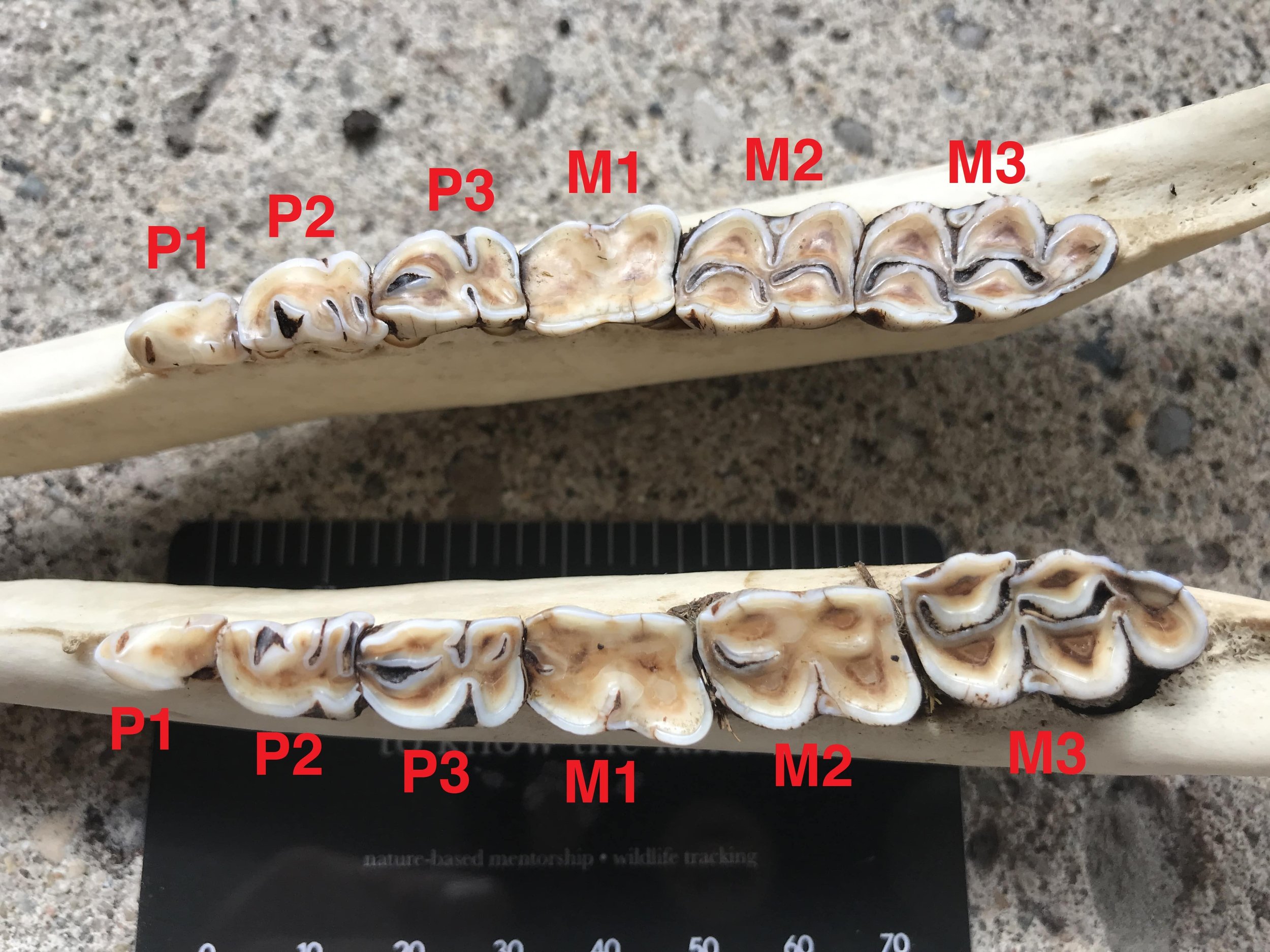

At the end of April I was attending a Track and Sign Evaluation. On the second day of the two day eval we came across a female White-tailed Deer carcass and were asked the question of how old the dead Deer was when she died. We were given three options to choose from based on what we could see. The three options were: A) 1-3 years, B) 4-7 years, or C) 7 and up.

Well, when I got home I started I realized I had a lot more research to do.

Learning more about invertebrates and the signs they leave behind is such a valuable part of wildlife tracking to me. I feel like when I teach or share about the inverts, most people are kind of “cool, but where are the mammals?” about it, but I hope to keep learning more so that I can inspire some deeper respect and awe about a couple whole other phylums! There is so much life out there, that doesn’t look like us, move like us, eat, excrete, breed or breathe like us and every time I learn something new I get stoked. I am grateful to get to share some of that excitement in this post.

Throughout the past few years I have come across a few different large cocoons belonging to Silk Moths, who are large moths in the family Saturniidae, in the order Lepidoptera. As I encounter the cocoons I tend to look them up and try to learn something about them but eventually the individual identifications of each unique species is lost, except maybe the Cecropia. I wanted to write a short blog post, starting with the main three cocoons I encounter, helping to remember who makes which cocoons so I can better remember in the field.

Last weekend I was in Grey County helping with a mock tracking evaluation. At the beginning of our second day of the mock eval, I found a small bone near the edge of an old plantation. It was short, “hooked” at one end with a sharp chisel like edge at the other end. There appeared to be a couple of points where the bone could articulate (connect) with other bones in whoever’s body this bone belonged to. Along a flat surface of the bone there were small thin ridges which I ran my finger along, over and over as I wondered as to which animal the bone may be from? I knew I would have to look into it more.

For a few years I have come across a gall on Spruces all over the Eramosa River Valley. Most of the Spruces are Norway Spruces , but I have also found them on White Spruce. They were mysterious to me so I looked them up a couple of years ago and learned that they were called the Pineapple Spruce Gall, or Spruce Pineapple Gall, or Eastern Spruce Gall depending on who you’re asking, but that was where my knowledge ended. Recently, after coming across them again, I decided I needed to learn a little bit more about them.

This past Saturday was another outing with the Earth Tracks Wildlife Tracking Apprenticeship. We went out to the Kinghurst forest in Grey County, Ontario to see what we could find together. It was a small group of six of us, but that made it a little bit sweeter as we could really dig in to all of the things we were seeing.

While in Algonquin Park this past week with the Earth Tracks Winter Wildlife Tracking Trip I tried to pay more attention to some of the bird sign throughout our days, though I didn’t always get some good photos, and I missed recording some beautiful songs and calls. I will share however what I did find in the park and what I have been able to learn thus far.

On one of my tracking study calls a photo was presented and everyone was asked to identify the bone that was shown. Somehow a few people were able to identify it rather quickly. I had never heard of the bone before but took note. I love learning about the skeletal structures of animals and spend a lot of time on it, but how did I miss a bone that so is so important to an animal, and that so many others knew? I needed to learn more about this bone.

We had just crossed over from the thick White Cedar forest into a little more spacious deciduous forest, when, in a very unassuming tone, a friend called us over to check out some tracks. I don’t know if he realized at first how cool the trail he had just found was, but as we stepped off of the path and looked down at the tracks everyone leaned in a little closer, and our voices started to ring with a little more excitement. Our colleague had found a Fisher trail.

I went for a walk by myself the other day to scope out an area I was going to be going with some students. I wanted to see which areas would be worth investigating and get a sense of how long it would take to get to different landmarks I thought might be worthwhile to go with them. While I was out in a part of the forest I didn’t even consider would be that interesting, I came across a bone, or a series of bones rather, which I wasn’t familiar with. I had to take some photos and knew I would be looking it up when I got home.

I have been thinking a lot about bones lately.. I guess I think a lot about bones all the time, but lately I have been trying to consider them more completely, in relation to one another, and to better be able to identify which bones are which, where they come from on the body, and which bodies the particular bones I find make up? There are so many questions that come wrapped in bone that it’s kind of fun to take the time to consider some of them.

A lot has been studied and written about on the topic of White-tailed Deer. But despite reading a ton of it, I still find it trying to find all the various pieces of information and put it all together, unless I write it up myself. Here is my attempt to consolidate and better understand how we can come to know a deer’s age at the time of their death by looking at the teeth which remain.

I wanted to compile a list of some of the common galls one might encounter here in Guelph, Ontario. I have been spotting a few lately and wanted to build a little database for myself and for others who may encounter them and want to know a little more. The galls are named by the inducer, and what I mean by that is the insect as all galls below induced by insects. I hope to make a series of posts over time.

“to know the land” is an assemblage of varied projects inspired by decolonial thought and action, ancestral tradition, and the work of many writers and teachers, seeking to evoke resilience, resistance, and reverence for the land.

to know the land is a collection of projects by byron murray.

It’s always nice to have a few days off during this time of year. While a lot of folks are busy with family, or having cozy times at home, I can wander through the snowy woods looking for the signs and tracks of all the other animals who we share the land with.

Sharing some stories of some of the trails I have been on over the past week, detailing some of what I have been observing and learning. Fondling icy Coyote tracks, to learning about a new species of Poison Ivy (new to me), to finding a flayed Cottontail carcass, it’s been a ton of fun this past week.