Two Coracoid Bones

The coracoid bone of a bird, found in Grey County at the Valley of Three Bridges, 2024.03.17.

Last weekend I was in Grey County helping with a mock tracking evaluation with folks from the Earth Tracks Wildlife Tracking Apprenticeship. This year I got to help with the other side of things. I was assisting with looking for tracks and sign left behind by all sorts of animals and coming up with a question to offer to those who were participating in the evaluation. It was mimicking the evaluations done by Tracker Certification North America/Cyber Tracker and was a lot fun. We pointed out some galls, some Raccoon (Procyon lotor) tracks, Red Squirrel (Tamiascurius hudsonicus) feeding sign, as well as questions regarding a fairly fresh White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus) corpse we discovered in a lowland White Cedar (Thuja occidentalis) forest.

At the beginning of our second day of the mock eval, I found a small bone near the edge of an old White Pine (Pinus strobus) plantation. It was short, “hooked” at one end with a sharp chisel like edge at the other end. There appeared to be a couple of points where the bone could articulate (connect) with other bones in whoever’s body this bone belonged to. Along a flat surface of the bone there were small thin ridges which I ran my finger along, over and over as I wondered as to which animal the bone may be from? My immediate thought was that this bone was from a bird, and that it was a coracoid bone. Which bird? I thought that it must have belonged to a Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo). The bone was so big that this seemed to be the only bird who might live in a woodlot like this. I showed it to my co-mock evaluator Alexis Burnett and he too thought it was from a bird. We both agreed that this was likely from a Wild Turkey based on the size, but that I should look into it more.

Turns out I was right… sort of. It was a coracoid, one of two, which are a very important bones for birds. The coracoid is the largest bone in the shoulder joint. The coracoids’ function is like that of a strut or a column. It is a structural component of the pectoral girdle and works by resisting longitudinal compression of the chest cavity by the pectoral muscles when the wings push down. The coracoids protects the lungs from being crushed by the sternum every upstroke of the wings. The supracoracoideus muscle stretches over top of the coracoids and pulls on the humerus bone, causing the wing to lift. This pull of the bone would also compress the lungs if it weren’t for this skeletal brace holding the sternum back. Additionally, when the pectoralis muscle pulls down on the humerus bone this causes the wing to come downwards in a powerful downstroke, spreading and building tension in the furcula, and enabling the bird to lift away from the ground. If it weren’t for the coracoids, the humerus bones would hit the sternum with every downstroke of the wing. Imagine a room where the ceiling and connected walls are constantly pushing in on themselves. As they repeatedly smash into each other the amount of damage increases. But imagine we installed some columns to support the ceiling from smashing down on the floor and bracing the walls, preventing them from buckling or beating against one another. This is the role of the coracoid bones. A strong column bracing the pectoral girdle of the bird.

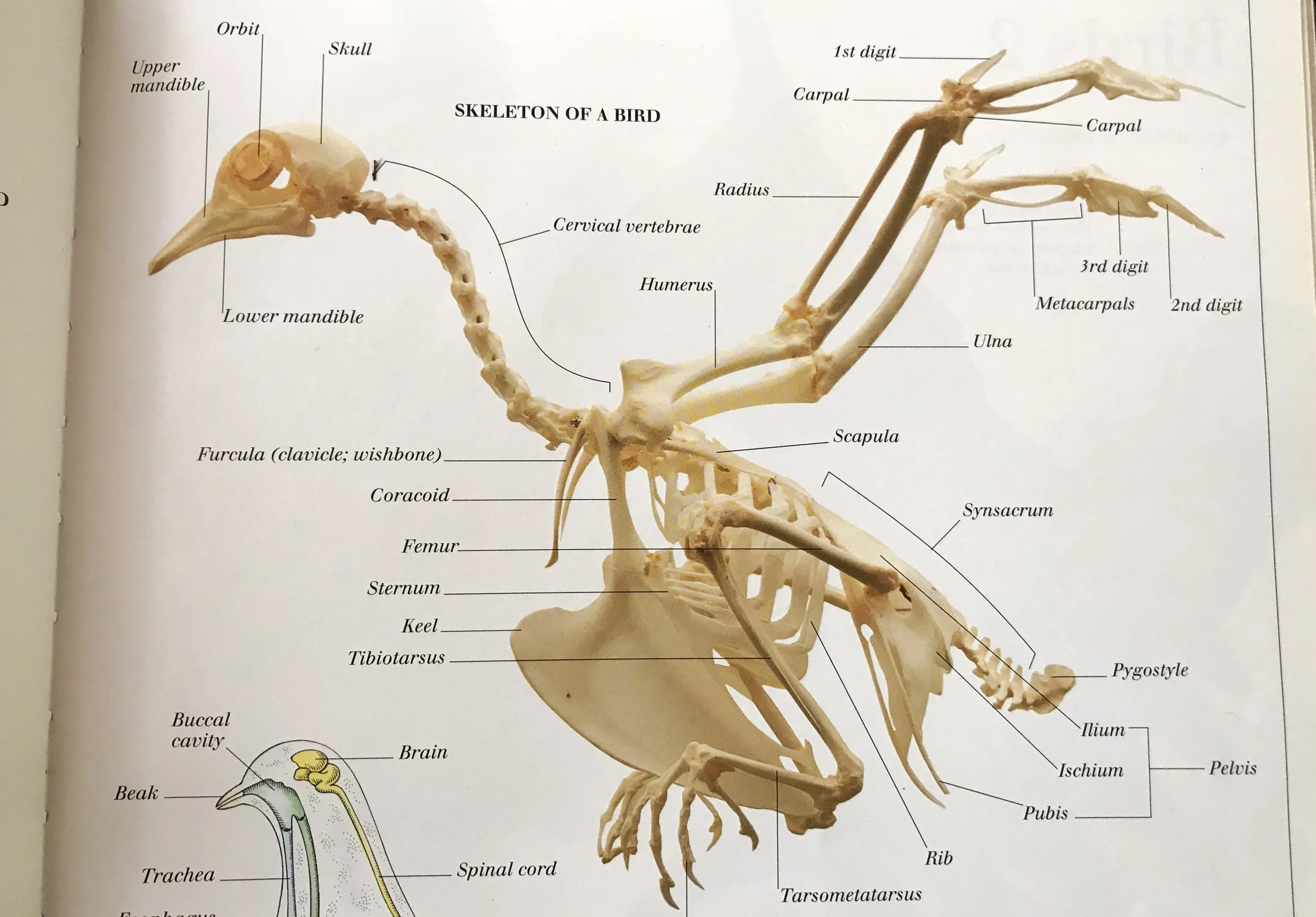

Image of bird skeleton, from “Eyewitness Books” series, title and date published, unknown.

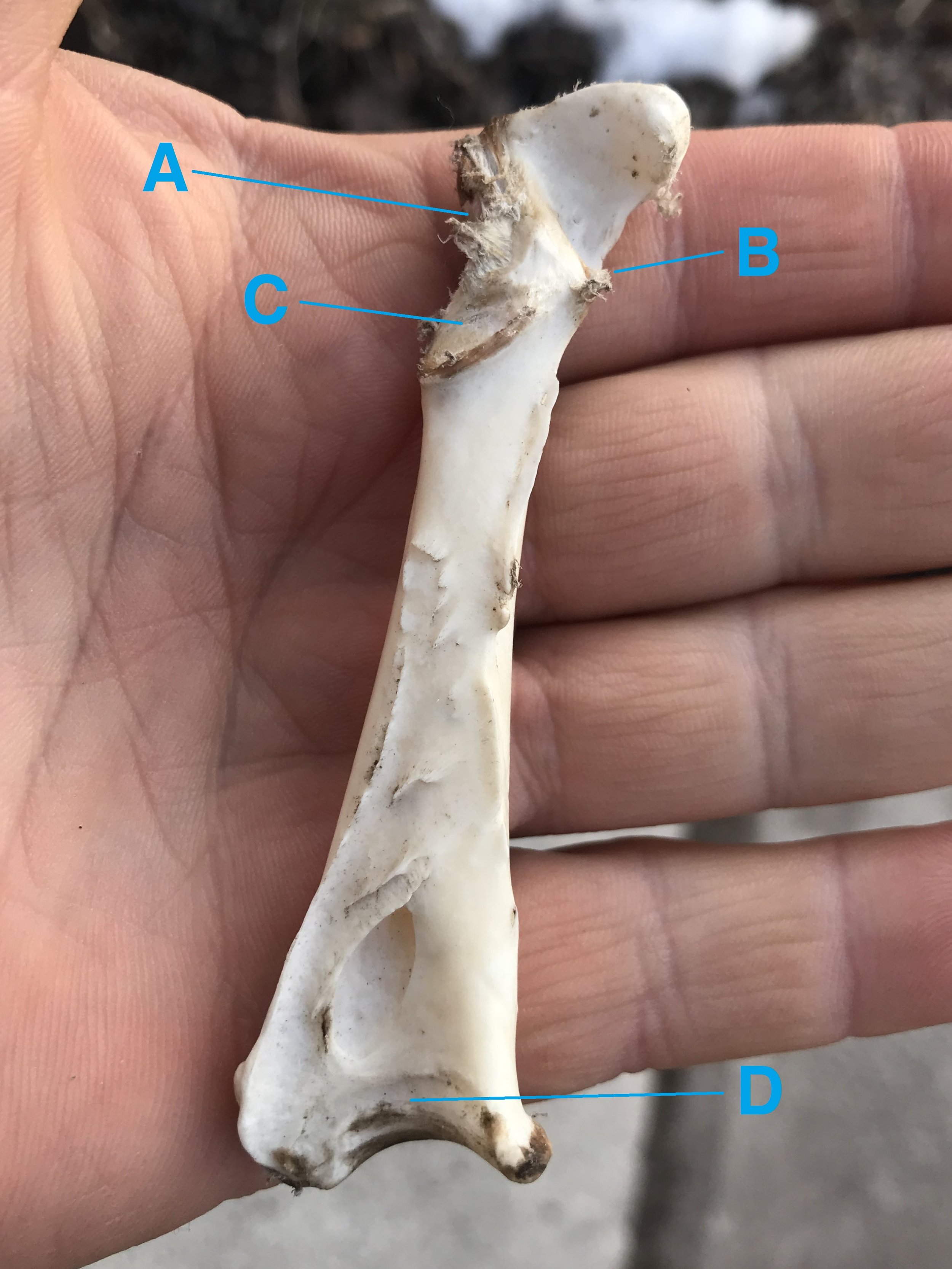

Its sternal end is quite broad, making the bone look a bit like an isosceles triangle, wide at the base and tapering somewhat as you move up to the superior end of the bone towards the articulation with the furcula or “wishbone”, as well as the scapula, or shoulder blade. That broad base of the coracoid pictured at the top seemed very interesting to me. I assumed it would be a helpful feature in identifying the species, and I was correct.

Canada Goose coracoid from Avian Osteology by B. Miles Gilbert, Larry D. Martin, Howard G. Savage.

When searching for coracoid images online I first tried Wild Turkey, as that was our first guess, but our bone didn’t match the images. I then looked for other birds which might have been in the area, including Canada Goose (Branta canadensis) which is another large bird which is very common in the area. Many of the images I found looked just like the bone I had in hand. Not only were the images a match, but I found a 3D model which I could rotate and see all of the angles mirroring the bone in hand. This was exciting. I now knew the identity of the bird where the bone had come from! I measured the coracoid and it came in at 81 mm (3¼ in) long. When I referenced the book Avian Osteology (Gilbert, Martin, Savage, 1996) it seemed to be in the higher end of the range for Canada Goose, but fit right in for the look of the coracoid from the right side of the body.

My next thought was that if I had properly identified the one coracoid I should practice identifying others. I knew of a bird skeleton which I had gone to with my students a couple of times over the past year. I figured I could go and see if there was a coracoid bone I could retrieve and try and identify it, even if I knew which bird it was from.

What I figure is that a Wild Turkey was hit by a car and then dragged away from the road and into a grove of White and Norway Spruces (Picea glauca and P. abies) by a Coyote (Canis latrans). The Coyote ate what they could and the remaining bones were discovered near the Spruce grove, mostly cleaned. The carcass was originally found on October 17th, 2023, and the photo above was taken on February 7th, 2024. Luckily one of the corcacoids (circled in red) was still attached with a scapula.

Knowing that this coracoid had come from the skeletal remains of a Wild Turkey which had been seen when the identifying feathers were still attached to the ulna and radius, I searched online for images of the coracoid of a Wild Turkey and found them accurately matching the one in hand. The size of the Turkey coracoid is 93 mm long (3⅝ in). But how could I determine which side of the body this one was from? Turns out Avian Osteology had a simple procedure to find out.

The authors suggest that you hold the coracoid with the sternal end (broad end of the bone) facing you, with all of the facets (grooves where other bones fit) facing up. Next you have to look for the humeral facet. If this is on the left side on the bone, then the bone is a left. If it is on the right side of the bone, then it is from the right side of the body. The procoracoid process is pointed toward the middle of the bird’s body, which means it is facing opposite the side that the bone is from. Let’s look again at the coracoid from the Canada Goose.

A : Humeral facet

B : Procoracoid process

C : Scapular facet

D : Sternal facet

When I look at the bone in hand, and notice that the humeral facet (A) is on right side of the bone, and that the procoracoid process (B) is facing the left side, then I know that this is a coracoid bone from the right side of the body.

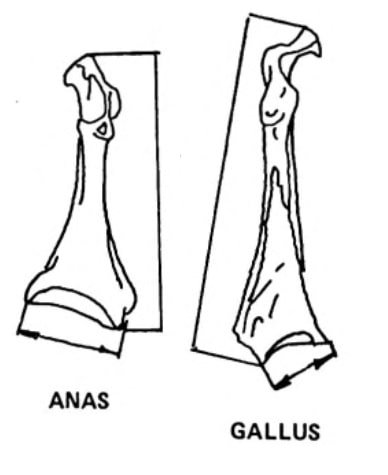

Let’s try that again with the Wild Turkey coracoid. I bet you can figure it out before I name it. The humeral facet is kind of shallow on Galliformes and, on this bone in particular, kind of invisible due to the remaining tissue, but the procoracoid process is sort of visible, and facing right, meaning that the Wild Turkey coracoid is from the left side of the body.

A couple of additional cool things I have learned about the Wild Turkey coracoid is that you can sex the bird based on the size of the bone! The male range for Wild Turkey is about 101 - 117 mm (4 - 4⅝ in) and the female range is 84 - 95 mm (3¼ - 3¾ in), which implies that the coracoid I found was from the skeletal remains of a female.

I found it tricky to figure out the correct way to measure the coracoids so I ended up going back to Avian Osteology, and of course I had missed the very clear and simple diagram. I have included the relevant section of the diagram in the gallery after the diagrams of the coracoids.

I recently got to visit a dead Cooper’s Hawk (Accipiter cooperii) which was found in the woods by some colleagues. I was hoping that I could get to check out the coracoid bones but when I arrived I noted that the Coop had been eaten from the neck down and was missing the pectoral girdle. It got me thinking that hopefully sometime soon I’ll come across another coracoid I can try to identify. Every new bone gives me insight into the biology, life history, form and function of the animals they belonged to. I can start to see the world through different lenses and with new insights as to how different pieces fit together. Every insight brings greater depth to the awe and wonder I have for the Earth and all the forms of life this planet holds, and for that I am extremely grateful.

To Learn More :

Tracker Certification North America

Avian Osteology by B. Miles Filbert, Carry D. Martin, Howard G. Savage. Missouri Archaeological Society, Inc., 1996.

Manual of Ornithology by Noble S. Proctor & Patrick J Lynch.