Wolf Trees, Stink Horns and Carrion Beetles

Another day with the tracking apprenticeship and damn, was it a blast! Our focus was how we can read the changes to the landscape based on the signs which remain. This included looking at the open relatively flat field that you see in the photo above. This can be a sign historical use of this field for grazing animals, and possibly even some occasional plowing. We encountered a couple of large rock piles in the field which pointed to where the farmer once piled the rocks which were brought up to the surface by the shifting freeze and thaw of soils.

The woods adjacent to the field held some massive Sugar Maples (Acer saccarinum) with broad trunks, wide outstretched branches, taking up a lot of space in the canopy, looking very much unlike the rest of the trees growing around them.

These trees are known colloquially as Wolf Trees, or Pasture Trees. They are the remnant trees which were allowed to remain when settlers were rapaciously clearing the lands to make space for grain, cattle, and Eurocentric ways of life. The forests were cleared but for a few odd trees which left behind to allow for shade for their cattle on hot Summer days. Since these trees no longer had the company of other trees, they no longer had to singularly reach upwards for a taste of sunlight. The light was all around them. To maximize sunlight collection in a newly open environment, the trees spread wide their branches and grew these wide stretching canopies. Over time the fields were abandoned and the forests returned. As new trees came up they all reached for the light and growing broad canopies wouldn’t be an efficient way to collect sunlight. Instead they all grew in tall, with narrow canopies, but still these occasional older trees remained and still remain, bearing the forms afforded by abundant light. Nowadays these trees are taking up space in the canopy, often to the detriment of any new sapling that tries to grow in their shade, but still life abound. The heart wood of many of these big trees have begun to rot out, and the resulting hollows provide abundant habitat for small mammals and cavity nesting bird species. Even other plants, such as mosses and the Currants (Ribes spp.) we saw, can grow in the crotches of their immense branches. Wolf Tree researcher Micheal Gaige has written a lot on the value of these home trees to wild life.

Further into the forest closer to the cliff edges, amidst the Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) scratches where they scuffed up last years leaf litter looking for seeds, bugs, and roots, we found some wind fallen trees with mounds of sand where the roots would be.

These windfall trees are fundamental to healthy forest ecosystems. As with all things when they die, they make life ever more possible. Insects burrow and excavate galleries under the bark and throughout the entire tree. Lichen soredia, moss and fungal spores deposited by wind and dropped from animals scurrying along the bark soon “take root” and infiltrate the wood, furthering the decay by holding moisture and providing habitat and food for more animals and plants to grow. Woodpeckers come to feast on the growing number of insects who now call the tree home. Cavities develop where larger birds and mammals move in, make nests, bear and raise young, and leftover minerals and nutrients in their scat feed the bacteria, fungi, lichen and mosses. New seeds sprout where deposited by passing vertebrates, or dropped by trees nearby.

Alexis explaining the pits and mounds.

Looking at the mound and beyond down the trunk.

As for when the root mass starts to decompose it drops the soil stilled lodged within the tangles large and small, creating small hills of dirt and the material from the decomposing roots on the forest floor. These are called pillows or mounds. The hollowed out pit where the roots once sat can fill with water during heavy storms, and make space for breeding insects to lay their eggs, for small invertebrate homes, for amphibians and small mammals to feed on the inverts, and on an on throughout the trophic webs of older forests. These are called cradles or pits. When a forest landscape is full of these pits and mounds, we can see the signs of a healthy old forest that has historically had little logging (trees usually need to be standing to fall and pull their roots out from the earth), or plowing (the mounds and pits would be flattened and the forest floor more level and even). It really is tracking the history of the landscape when we look/listen to a forest like this.

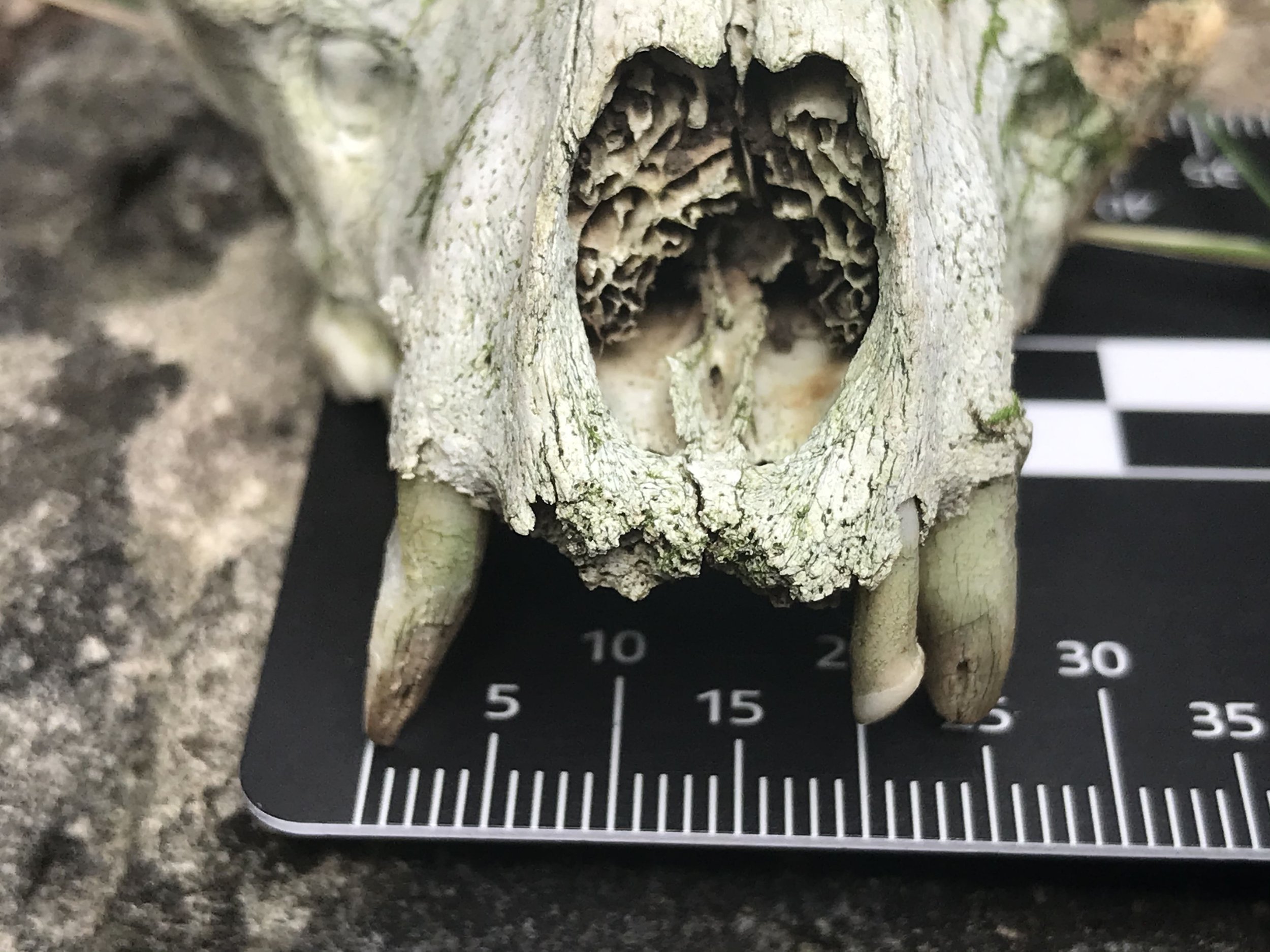

I can’t remember who found it, but before lunch at some point someone showed us all a skull they had found. I quickly identified it in my mind but asked if I could carry the skull for a while so I could take some photos specifically for this blog post.

When I find skulls of this species I look for a couple of different things. First, I look for overall size. This skull fits in my hand snugly. I cannot close my fist around it, but I can grasp it well even if I cannot close my fingers around it. I then look to features of the overall shape. I see a short rostrum or snout, forward facing sockets where the eyes would be, and when looking at the large brain case in comparison to the rest of the skull I always see the shape of a lightbulb. I know others see this too and it is a pretty good tell if you have enough of the skull intact.

I look to the teeth next and I look to see if any teeth are remaining, and if so what do those teeth look like? Are there canines? Are there large incisors? Something like 40% of mammals on Earth are rodents and they wouldn’t have canines and would have larger incisors. If I can cut out the rodents, then I can skip a chunk of the animals who live near me. Sometimes these skulls come with no teeth and that makes things a little harder to tell who the skull belonged to. I think it is important to look for teeth if there are any, but also learn to look at the rest of the bones which make up the skull as well because often we find partial skulls due to how the animal died, or who fed on the animal or their bones after the animal died. If the teeth are missing but the rostrum and tooth sockets are still present, you can imagine the canines and the distance between the two upper canines. Now imagine the canines coming down and if the distance between the sharp pointy tips of the teeth would come in around 2.5 cm or 1 in (lesser in younger or females, more in larger females and older males), then this too is a giveaway of this species.

I think I am going to leave this one unanswered but there are lots of ways to find out who this skull belonged to.

After lunch we began making our way down a deep crevice along the cliff wall of the Niagara Escarpment. Some year I will bring a large ball of twine to measure the depth of this crevice, because it’s totally amazing.

At the base of the fissure laying, atop of a layer of old fallen debris from the Eastern White Cedars (Thuja occidentalis) above, laid the body of an Eastern Cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus), likely dead for about a week. I say for about a week as the eyes were missing, the body was limp, and the underside of the Cottontail was definitely very stinky when I pulled them back from the Cedar leaf litter. But definitely more exciting than finding a dead animal was finding the animals which eat the dead animals!

As I looked down at the leaf litter, I noticed quick movement and a small flash of orange and my heart began to sing. My hand shot so fast into the gooey death stenched Cedar leaves faster than anyone could see. Before anyone registered what I had done I was cradling a critter in my closed palm and I felt them defecate their lunch of corpse into my palm. Again kids, never do as I do.

I rushed past everyone, all who were patiently kindly waiting for everyone else to make their way out of the narrow crevice. Perhaps I was too excited but to encounter a member of one of my favorite animal groups.. well I get a little stoked sometimes.

It was a Carrion Beetle from the Nicrophorus genus. I could tell right away from the orange and black patterning on the elytra (wing covers). I really couldn’t tell the species because they were moving so fast. My hope was it may be a Nicrophorus americanus or American Burying Beetle, a rare and critically endangered species which has been found in the Great Lakes region in years past. I had never seen one before! Could it be? It was only until I got home and looked up some photos of the N. americanus that I realized that no this is not them. The pronotum (the shield looking plate behind the head protecting “the neck”) of a N. americanus would have a orangey red blotch, which seems to be pretty distinctive and a characteristic no other Nicrophorus species on Turtle Island/North America have. I got to wondering who then was this? I pulled out a treasured book, “The Insects and Arachnids of Canada” pt 13 : The Carrion Beetles of Canada and Alaska and read the description for one of the more common Nicrophorus species, N. sayi. The species description noted that N. sayi has three orange segments on the end of the antennal club, and the final segment is black (a). Another differentiating feature is that N. sayi have a really incurved hind tibia, which you can sort of make out in the photo above (b). I have learned before that N. sayi does generally inhabits both open and woodland habitat, though especially the latter with conifers, so this would also make sense for the area that we were in. I hope to be able to remember this when in the field and when I am full of excitement. I really do love these carrion beetles.

I took a moment to wash my hands while everyone moved along and examined the American Hart’s Tongue Fern (Asplenium scolopendrium L. var. americanum) which has been on the Species at Risk in Ontario list, listed as “special concern” since 2008. I believe I have only seen it at Mono Cliffs, and perhaps seen the eurasian subsp. scolopendrium in a garden centre or greenhouse somewhere.

Outside of Ontario, A. scolopendrium is considered endangered. The Hart’s Tongue Fern tends to grow on moist mossy limestone rocks under the deep shade of deciduous trees, which was exactly the habitat we were moving through at the base of a cliff wall of the Niagara Escarpment. The fronds are wide and not divided like many other ferns, and because of that, unlikely to be confused with any other species in Ontario.

I was looking forward to seeing the Hart’s Tongue and it was great to know they are still doing well at this particular location. I feel like, and this may be wrong to assume, someday I’ll come to the spot and see a lot of the individual Hart’s Tongue plants uprooted or destroyed by folks who may not know how rare or particular this plant is, so it is a treat to return a couple of years after first meeting them and seeing the fronds amid the moss and fallen leaves.

Almost directly beside the ferns was a different special discovery. Amidst a jumble of mossy rocks, on top of one rock maybe 20 cm (7⅞ in) high was a flush of black, blue, and white feathers strewn about. The black lines cutting across the blue vanes, many with white tips.. this looked like a Blue Jay (Cyanocitta cristata) got got. All the feathers were contained on top of the rock, maybe 30 cm x 50 cm (11¾ x 19¾ in) and I don’t remember seeing feathers on the ground beyond the rock. It looked like a possible kill site but because the feathers were so contained in the area I would assume a mammal, and because the surface space where the mammal tore apart the bird, I would say it was likely a small mammal that did the dismembering. If it were a perching bird of prey that did the tearing apart, the feathers would likely have fallen from the perch in a wider area than what we found there on the rock.

The other thing we noticed on the rock was a foot, likely from the Blue Jay. The foot measured 4.5 cm (1¾ in) long, and appeared to be fatter towards the metatarsal and then narrow towards the talons. This reminded me of the morphology I often see in Common Raven (Corvus corax). I got to wondering if the Common Raven was more closely related to the Blue Jay than the American Crow (Corvus brachyrynchos) was? In retrospect, this doesn’t make sense as the Raven and Crow are both in the Corvus genus while Blue Jays are in the Cyanocitta (along with the western Stellar’s Jay, Cyanocitta stelleri). But I am still wondering what was is it about their ecologies that would have shaped the feet of Common Ravens and Blue Jays to be of a similar structure, but different from American Crows? I don’t know if I have the skill to figure that out right now, but it is something I will keep in mind.

In addition to the feet I got really excited when someone mentioned that there was also a skull found. A Blue Jay skull? Likely. How do we know?

According to the book Bird Tracks and Sign (Elbroch, Marks, Boretos, 2001) the overall length of a Blue Skull comes in around 5.4 cm (2⅛ in) long. The skull pictured about was about 5.6 cm (almost 2¼ in). The average bill length of a Blue Jay in the book was 2.2 - 2.4 cm (⅞ - ~1 in) which is roughly 41 - 44% of the skull length. The bill on the skull we found? 2.3 cm. Elbroch, Marks, and Boretos write that the cranium of a Blue Jay measures between 3 - 3.2 cm (1 - 1¼ in). The cranium of bird skull we found on a pile of Blue Jay feathers? 3.2 cm! Does a Blue Jay have a blackish bill? Yes, they do! IS IT A BLUE JAY SKULL??? Yes. Yes it is. Pretty cool!

I have a big affinity for skulls and they mean a lot to me. To come across the skull of an animal which is so ubiquitous, but I don’t often find their remains, that’s pretty special. I was already riding high from the Hart’s Tongue sighting, and now this! Things couldn’t get any better… but wait! There’s more!!

I got called over to help confirm a mushroom find, which happened to be a Stinkhorn! A Phallus ravenelii if we want to get down to species, and they were in the prime of their short lived fruiting body life. There was even another Stinkhorn still in the egg phase of their life cycle. A few years ago, at this same location, we had found another egg, but wasn’t sure who/what it was until we cut it open and then it was clear. But now to find both the egg and the mushroom, I was totally stoked.

After the mushroom find there was more amazing stuff. For the third time in my life I encountered a Yellow and Black Flat-Backed Millipede (Rudiloria trimaculata) which had been infected by a parasitic-zombie fungus called Arthrophaga myriapodina! Arthrophaga myriapodina is a parasitic fungi that infests these millipedes, starts controlling the millipede bodies and making the zombie millipede climb to a high point where they eventually die and release a bunch of spores into the forest to find new potential zombies and begin the cycle anew! Nature is so bad-ass.

We stopped for a bit to check out some scat (which I will get back to below), but then we moved on a little and did a short sit spot. I ended up crossing the wide beautiful ravine we were walking through towards the other wall. I tucked in against an old fallen Paper Birch (Betula papyrifera) and looked out across the shady mostly Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum) forest and then back to my sit spot when I noticed some of my fav looking mushrooms growing out from the end of the busted Paper Birch. They were Pholiota’s of some kind. Pholiota is a tricky genus where it’s hard to get down to species for some, but I think these are Pholiota aurivella.

Now, back to the scat.

I found this scat at the base of a tree stump, in two pieces, with a small third piece off to the side. It was very dark, with shiny bits that either looked like Grape (Vitis spp.) skins or insect parts. Both would be possible, and couldn’t entirely make them out, though I was leaning towards insect parts because if it were Grape skins, we would also likely be seeing Grape seeds, of which I couldn’t see any. The measurements of the largest piece was 3 cm long x 1.5 cm wide (1⅛ in L x ⅝ in W). I asked people to look at the scat and come to a conclusion before we discussed together, sort of mimicking a tracker certification evaluation in our process. Everyone took a look and then came to a conclusion. It seemed there were three possibilities folks had been thinking about; Raccoon, Striped Skunk (Mephitis mephitis), or Virginia Opossum (Didelphis virginiana).

To be honest, I have never knowingly seen a Virginia Opossum scat before. Most of the books I have also have short entries on Opossum scat pretty much just saying that due to their highly diverse diet their scat ends up being incredibly variable and can look like a lot of other animals scat. Of the few photographs I am finding online, it seems like Opossum scat is tubular at times, though can be a lumpy tubular or a number of tubular scats all compressed into a longer log, sometimes with a bit of a twisted look to them but not always. In Mammal Tracks and Sign by Elbroch and McFarland (2019) they write that Opossum scat is “surprisingly difficult to find and identify”, though usually loose and soft. They also mention that for captive Opossums, there is commonly hair in it from them grooming themselves. The scat we found was hard, tough, and had no signs of hair. I conclude that this is not Opossum scat.

Raccoon is always a likely bet in our neck of the woods. Being so close to Tkaronto/Toronto, which is the Raccoon capital of the world, we need to always consider Raccoons when we find tubular scat at the base of trees or on stumps. Raccoons commonly leave multiple scats at the base of trees and stumps, but when I usually find a few different Raccoon scats, they are usually made up of different materials and different ages. Raccoon scats can definitely be found at 1.5 cm (⅝ in) in diameter, but rarely come in at less than 8.5 cm (3⅜ in) long. If I added up the length of all the pieces we found it would likely just reach 8 cm (3⅛ in) in length. Raccoons eat nearly everything they can get their crafty hands on, including Grapes and insects, so content wouldn’t make a difference. The size and general appearance didn’t feel too Raccoonish to me. It seemed a little too irregular, not enough variation, and too small. I conclude that this isn’t Raccoon scat either.

Striped Skunk scat is similar to the scat of the two species above in that it can be variable, both in content and form, but are generally tubular with blunt ends. They also seem to break apart kind of easily. The size, according to Elbroch and McFarland, ranges from 1 - 2.2 cm in diameter x 5.1 - 12.7 cm long (⅜ - ⅞ in D x 2 - 5 in L), which fits the scat we found. In Winter, when I am trailing Skunks in the snow, I often see their trails loping about from tree trunk to tree trunk looking at the base of the trees for… I’m not sure. But when I saw this scat at the base of this stump I immediately thought of the Skunks. Elbroch and McFarland also note that Skunks will deposit scat at the base of prominent features on the landscape, like stumps. Again, considering the content, Grape or insects, Skunk would make sense, but it would be a lot more convincing if the content were mostly insects, even if Skunks eat a lot of whatever. So, I placed the scat on a fallen log beside the stump and crushed it gently to see what it was made of. Looks to me like a whole lot of Beetle wing covers (elytra).

The end of the day at Mono Cliffs usually ends by climbing a less steep area of the escarpment wall, and a short hike through a small forest and then back out to the Goldenrod (Solidago spp.) and Aster (mostly Symphyotrichum spp.) meadow where we first came in. We have done similar hikes to the one we did for many years, and while this could get boring, it doesn’t. The changes we get to notice, the familiarity with the landscape, the discoveries which build on things we’ve seen or found in the past, it feels like a reunion or homecoming in a way. It is a familiar place now, full of old friends and I get excited knowing that I am going for a visit every year.

I am deeply grateful to the land for making the day such a wonderful adventure. And sorry to everyone if I get a little too excited sometimes.. but really, how could you not?

To learn more :

The Insects and Arachnids of Canada, pt 13 : The Carrion Beetles of Canada and Alaska by Robert S. Anderson & Stewart B. Peck. Biosystematics Research Institute, 1985. (pdf)

Images of Blue Jay secondary and tail feathers

Bird Tracks and Sign by Mark Elbroch, Eleanor Marks, C. Diane Boretos. Stackpole Books, 2001.

Mammal Tracks and Sign by Mark Elbroch and Casey McFarland. Stackpole Books, 2019.