Tracking Birds At Saugeen First Nations, 2023.06.10

I want to start this post with a bit of a celebratory note. On April 3rd, 2023, after about 30 years in the courts, a judge ruled in favour of the Saugeen First Nation’s claim over the proper boundaries of their reserve. The boundaries include the Northern portion of the popular Sauble Beach. While the town of South Bruce Peninsula have decided to appeal the courts decision, I want to recognize and honour the long standing legal battle that the folks of Saugeen First Nation (SFN) have been fighting to have the boundaries recognized. I cannot imagine the celebration that must follow this decision and the affirmation and assertion of all of the hard work of the SFN elders and community members involved. Congrats to SFN, and if you would like to learn more, checkout this link.

We parked and got out of the vehicles after a long drive and took to the sand right away to find some good tracks. While we did discuss some Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes) and some Coyote (Canis latrans) tracks and gait patterns, I was really looking forward to finding some bird tracks. I was eager for the beach but James called me over to show me a track he’d found. It was from a bird! This was a great start to our day together as I came with the intention of tracking birds and we were only about four metres away from the cars. James, Alastair and I got down to check it out.

When I bent down I remembered how familiar it looked from a tracking outing I did by myself a couple of weeks ago, but with slight variation. I see a pretty classic looking anisodactyl (one toe back, three toes forward) bird track with the metatarsal (the point where all the toes converge on the bottom of the foot) very faintly making a print in the sand. We only found this single track, as the others left behind were likely run over by the cars entering the parking area. This track was roughly 44 mm (1¾ in) long when I measured it in the field, with a width of about 27 mm (1 in*) wide. I noticed that toe 1 (the toe facing the bottom of the image, also called the hallux) was pointing down and to the left, and toes 2 and 3 and 4 were splayed fairly equidistant. I also noticed that the tracks of the forward (the direction of travel would have the bird facing towards the top of the image) facing toes seemed to drag slightly creating a bit of a flared look to them. I have seen this flared toe print in a lot of photos of Mourning Dove (Zenaida macroura) tracks in sandy substrates, including in Bird Tracks and Sign by Mark Elbroch and Eleanor Marks (2001). I also read in Bird Tracks and Sign that the track measurements of Mourning Doves, 4.1 - 4.7 cm (1⅝ - 1⅞ in) long x 2.5 - 3.2 cm (1 - 1¼ in) wide, fit within the range of the tracks pictured above. They look similar to Rock Dove (Columba livia) tracks, but the tracks in the photo are shorter and thinner than the Rock Dove, 5.1 - 6.3 cm (2 - 2½ in) long x 4.4 - 5.4 cm wide (1¾ - 2⅛ in) . While working with the measurements and the overall look of the track, I believe this was left by a Mourning Dove.

I packed up my notebook, ruler, field guide and tape measure, and made my way down the path towards the beach where everyone else was already finding some good tracks.

When I arrived at the beach I saw that a few folks were scattered around on their own, but there was a larger group, looking at some tracks together. Soon I made it over to the big group, but I missed some of their processing over who’se tracks they were looking at, but I did check out the sand beside their popcicle sticks.

I noticed some larger tracks, which reminded me of Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) but they weren’t quite right. They didn’t seem as bulbous as I was used to. They were as large as some Wild Turkey tracks, but the stride, 46 cm (18 in), was lengthier than I was used to as well. The foot structure didn’t match the Turkey either because there was no hallux (again, toe 1) showing, and I have often seen the hallux on Turkeys. This left me with a blank as I couldn’t think of who else it would be. We have tracked Great Blue Heron’s (Ardea herodias) on this beach before and I would have thought them but toe 1 has reliably shown on the Great Blue trails I have followed. Who else was it? I think it was Alexis who suggested someone whom I never thought of. Sandhill Crane (Grus canadensis)! This would explain the long stride lengths, as Sandhill Cranes have quite long legs. Alexis also mentioned that they could be on the beach looking for something to eat. I ended up researching this later and Sandhill Cranes like to eat a wide variety of things including insects and other invertebrates, and if on land may consume grain, seeds, shoots and tubers, fruit, and even small vertebrates. Alexis noted that this time of year they would likely be tending to young as well which is kind of cute. Sandhill Crane bodies and calls remind me of Pterodactyls, and its cute to think of them walking around with their young yelling out their loud prehistoric rattling calls.

We ended up moving along and found a couple of other great mysteries before lunch, like the weird nickle-sized transparent jelly Danielle found in the water (a Pectinatella?), or the Frog tracks we spent so long deciphering, or even the Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina) trail likely leading towards the water, away from the beach. But really, I was there for the bird tracks.

The next track I really took note of was a single track along the muddy edge between the sandy beach and the Eastern White Cedar (Thuja occidentalis) forest. It wasn’t too big compared to the Sandhill Cranes, coming in at around 73 mm (2⅞ in) long x 63 mm (2½ in) wide. It had a fairly small imprint of the hallux at the back which was facing towards the right, which leads me to believe this is a left foot. I also noted the faint imprint of webbing at the tip of toe 3 leading towards toe 4. This is a very faint imprint, but was notable enough. I recognized the track as likely being from a left foot of a Mallard Duck (Anas platyrhynchos). Ducks often show the hallux in their tracks, and their feet are definitely webbed. Mallards are pretty plentiful as well, and if we follow “byron’s rule” it is important to first consider the most common animals in our process.

We continued on trying to make some distance as we hadn’t really gone far from the beach where we started out. It is sometimes very hard to get far when we’re tracking together as we keep finding all sorts of good spoor. I am grateful though, that this isn’t a hiking club, but rather a focused time for wildlife tracking with a dedicated crew.

I can’t remember what other folks were looking at when I decided to follow the pull of wonder and walk off again from the group, but I decided to head along the route closer to the Cedar forest than sticking closer to the water. Sometimes spreading out the group helps to find even more things to give a little focus to. Like an egg with the big hole in the side.

The egg looked like it had been predated as it was open from the side and the cracked pieces around the rim of the egg appeared to have been crushed inward. Usually when an egg hatches in the nest the parent birds will collect the egg remains and discard them away from the nest, though I have recently seen a post online where a photographer who witnessed some Sandhill Crane nestlings hatch, watched their parent consume the egg shells afterwards. The nestlings usually use their “egg tooth” which is a deciduous temporary projection on the bill which allows them to break through the egg shell and begin their emergence. They break through the egg shell in a single spot at first and then begin using the long sharp edge of the egg tooth to “unzip” the shell, usually in a straightish line along the diameter of the shell. This straight line cut along the diameter of the shell is a pretty good diagnostic of a hatched egg. Also, when looking at the shell remains, do the egg shell pieces along the edges appear to have been broken from the inside out, and are pushed out, or from the outside in? Confusingly, I have read that if you find egg shell remains where the membrane lining of the egg is folded inward this is a good sign of a natural hatching as the membrane rolls inwards as the egg dries out.

When we measured the egg it came in at 58 mm (2¼ in) long x 40 mm (~1½ in) wide. I ended up checking out the measurements when I got home, comparing with the numbers in Hal Harrison’s field guide Eastern Birds’ Nests (1975) and they came got pretty close to Mallard egg sizes. The book says the average Mallard egg size is 57.8 mm (2¼ in) x 41.6 mm (1⅝ in), which is near exact. The book also notes that Mallard eggs are indistinguishable from Black Duck (Anas rubripes) eggs… just to complicate things.

When it comes to trying to sort out who may have predated the egg there were a couple of things I looked into. We noticed two small holes on either side of the large opening on the side of the egg. They were both of near equal distance from the large main hole, coming in at 11 mm (~⅜ in) & 13 mm (~½ in) far away from the main hole. This was an interesting and insightful measurement. I have recently found other predated Mallard eggs with similar predation patterns with signs that pointed to Striped Skunk (Mephitis mephitis). We compared the egg we found with the diagram of predated Mallard eggs in Mark Elbroch and Casey MacFarland’s Mammal Tracks and Sign (2019), and noted an image with a similar pattern of entry along with two small canine holes on either side of a larger main hole, incredibly similar to our egg. This table we referenced from Mammal Tracks and Sign was developed by data and images from Interpreting Evidence of Depredation of Duck Nests in the Prairie Pothole Region by Alan B. Sargeant et al, (1998) which is a great resource on looking at predated eggs, especially Mallards. We also compared the distance from the two smaller holes to the main large hole with the inter-canine width measurements included in Mammal Tracks and Sign. They too seemed a match for Striped Skunk. In my own reading through Alan B. Sargeant et al’s paper I found some descriptions of Striped Skunk egg predation. They write “shells of eggs depredated by striped skunks [sic] usually have a large elliptical hole with coarsely broken pieces of shell caved inward” just as ours did. They also noted that “[c]ollectively, 102 (40%) eggshells had the opening in the side, 96 (38%) in a side-end, and 56 (22%) in an end.” Our find would fit with the largest pool of eggshells they found with the opening in the side. One thing they noted which stood out to me was that very few of the eggs depredated by Striped Skunks were found far from the nest. They wrote :

Skunks customarily ate duck eggs <1 m from the nest. Of 151 eggshells found at nests depredated by 3 captive skunks without a den near the nests, most (72%) were <20 cm from the nest. Eggshells were often in the nest, and few (4%) were >1 m from the nest.

While we found our egg close to the forest, in my very quick search of the area when we got up, I did not find any sign of a Mallard nest nearby. I admit to not looking very hard, but this could be a good thing to do next time I find a Mallard egg on its own.

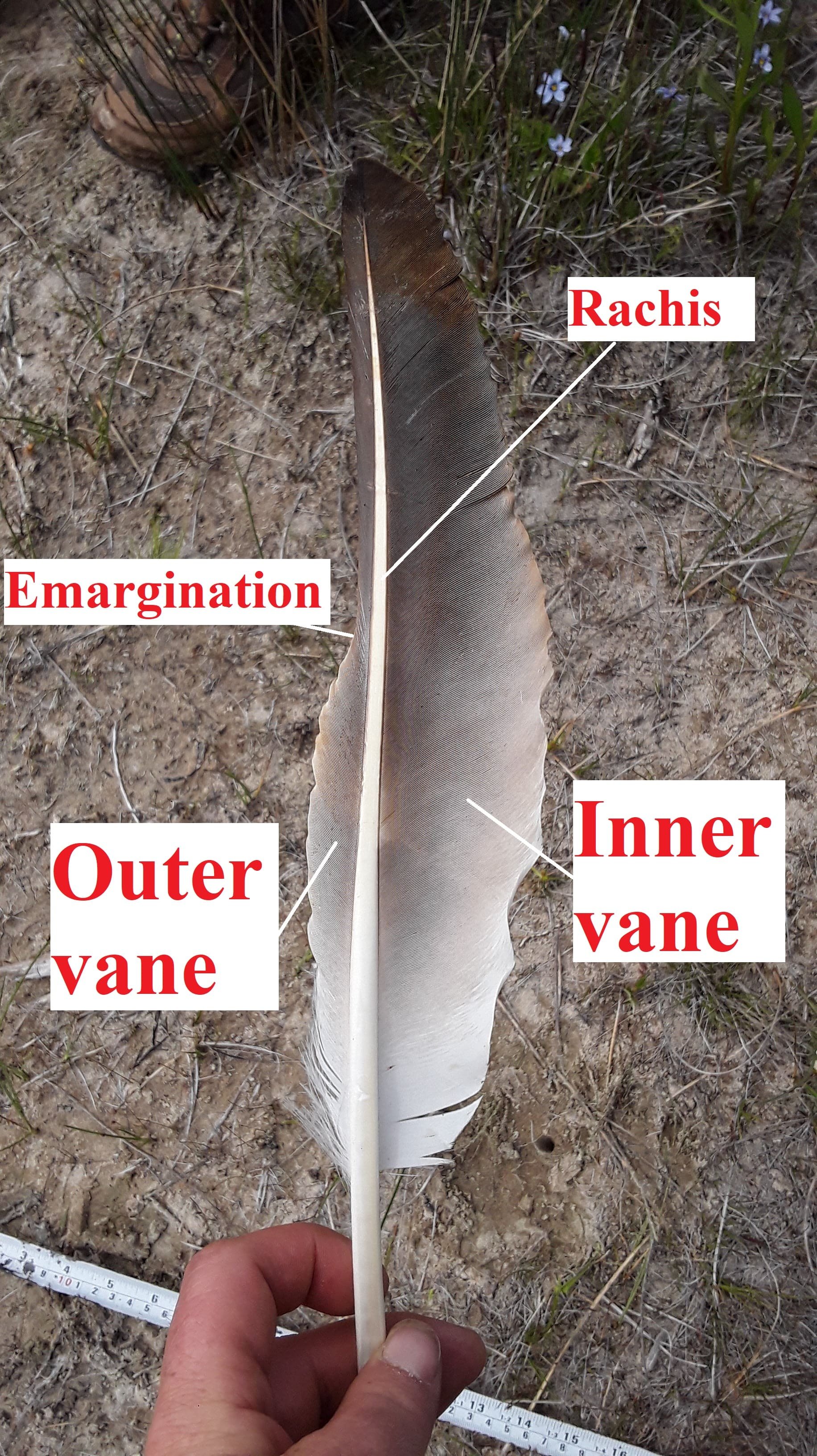

Sitting examing the egg took some time and luckily Yousaf got up to explore, and came back with a large dark feather. It was huge. I later measured it and it was 41 cm (16⅛ in) long. Not the longest feather I have seen but up there.

I am learning to tell where feathers belong on the birds bodies by looking at the structure and form of the feather itself. This particular feather looks to me like a primary flight feather from the right wing. Primaries are the feathers furthest from the body of the bird located on the wing, where we might think of as the “fingers” of the wing. This is indicated by the length of the feather, the emargination (how the feather looks narrow on one side near the top, but widens out as it gets midway down, and then narrows again as it reaches the quill), the intense camber (the arching curvature of the feather as seen in cross‐section - important for providing lift; not visible in the photos). I can see that the outer vane is narrower on the left side indicating that this is the side which would be facing the direction the bird is heading in, the leading edge. A good way to test this is to hold the feather and gently wave your hand horizontally through the air; one direction, the feather will flow easily, the other direction with give resistance. The direction the feather flows easily in is the direction the feather would be facing on the birds wing. From the size I got to thinking about Canada Goose (Branta canadensis) as some of their primaries have been recorded up to 37.4 cm (14¾ in) but it was missing an important feature of many waterbirds - the tegmen. The tegmen can be described as a long shiny patch on the underside of the primaries along the rachis, found on a few different kinds of birds including waterfowl like ducks, geese and swans. In Bird Feathers by S. David Scott and Casey McFarland (2010) they write

[T]he barbs of the primaries are uniquely specialized; lengthened, flat, folded toward the quill, and tightly overlapped, they create a strong glazed surface along the underside of the feather… These [waterfowl] are heavy and fast fliers: the tegmen area presumably reinforces the structural integrity of their primaries, keeping the vane from splitting during flight. This shiny patch readily distinguishes these birds from other families.

So lacking the tegmen we had to pivot away from a possible waterbird and consider who else was large enough to have such a large feather? Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus)? The feather we found was too small. Turkey Vulture (Cathartes aura)? The size fit, and they have long emarginated dark grey primaries with strong camber. When I got home and researched it, the size was correct as well. The feather was likely from a Turkey Vulture! I had seen some Turkey Vulture feathers shared recently on a tracking study call, but zoom calls don’t really capture the same feeling as holding this huge powerful efficiently built feather in your hand. I am very grateful to Yousaf for finding this and letting me bring it home to really study.

We went on with our day, finding so many more great things, like the keel (breastbone) of a large bird, a site of Blue Jay (Cyanocitta cristata) feathers strewn about on top of a old decayed stump (where Alastair also found a yet-to-be-identified Nicrophorus beetle!!), but as the day was wearing on, we had to head back to the cars.

When we got to the parking lot, Alexis invited anyone who wanted to to go back to the beach quickly to pick up some garbage before leaving. I don’t know who all went out, but as they did so, they all saw three large birds together in a group. It was a family of Sandhill Cranes, two adults and a juvenile. I didn’t get to see them but perhaps next time.

Instead of seeing the Sandhill Cranes, I went off to collect some trash by the parking area and to take a pee. As is the case sometimes, that urge to pee led me to a quiet place where some other animal had likely gone for privacy. A place where they may have dragged a meal… And all that remained though was the skull.

My first thought when looking at the skull was Mallard, again going with byron’s rule (consider most common species first). The rounded flattish bill without a curve, the slope of the nasal bones, and the overall size of the cranium. But when we got back to Alexis’ place and pulled out Animal Skulls by Mark Elbroch (2006) and Bird Tracks and Sign, we began to notice some differentiation from the skull in hand than the Mallard skulls described in the books.

We first noticed the size and form of the nasal apertures (nostrils) for the mystery skull were long, and broad, more similar to a Canada Goose than a Mallard, whose nasal apertures are shorter, and restricted to a little higher up on the bill. We then read in Animal Skulls about shelf-like orbital rims which the Canada Goose has but the Mallard does not. Mark Elbroch also notes the narrow downward facing post orbital processes (small bones behind the eye which stick out and help form the orbits where the eye would be) which our mystery skull had, Canada Geese have, but Mallards do not. The total length of the mystery skull when puzzled back together was 115 mm (just over 4½ in) which fits within Elbroch’s numbers in the skulls book for both Mallards and Geese, but just barely. Mallard skulls measured for the book peaked at 116.7 mm. Canada Geese skulls peaked at 125.4 mm (just under 5 in). Considering average lengths as being most common, the more mid-range the measurement the more credence I give it. I don’t think this is a sound scientific practice, but makes sense to me. So in light of the measurements, the narrow downward facing post orbital processes, the shelf-like orbital rims, and the long and broad nasal apertures, I think this is the skull of a Canada Goose.

After we identified the skull, we put the books aside to get ready for a meal together, one of my favourite parts of our weekends together. It’s always a blast to practice this tracking craft in community, pushing each other, learning together and doing the research when we get back home to deepen the knowledge who and what we encounter on the land. Thanks to everyone who helped to point out tracks, to take measurements, who asked questions and who suggested answers. What a great day.

*a note on inch measurements: all fractions of inches have been rounded to the closest eigth of an inch (⅛).

To learn more :

Saugeen First Nation Update regarding land claim victory

Bird Tracks and Sign by Mark Elbroch and Eleanor Marks. Stackpole Books, 2001.

Eastern Birds’ Nests by Hal Harrison. Houghton Mifflin, 1975.

Interpreting Evidence of Depredation of Duck Nests in the Prairie Pothole Region by Alan B. Sargeant et al, 1998.

Mammal Tracks and Sign by Mark Elbroch and Casey McFarland. Stackpole Books, 2019.

Bird Feathers by S. David Scott and Casey McFarland. Stackpole Books, 2010.

Animal Skulls by Mark Elbroch. Stackpole Books, 2006.