A Basic Guide to Non-Human Mammal Dentition

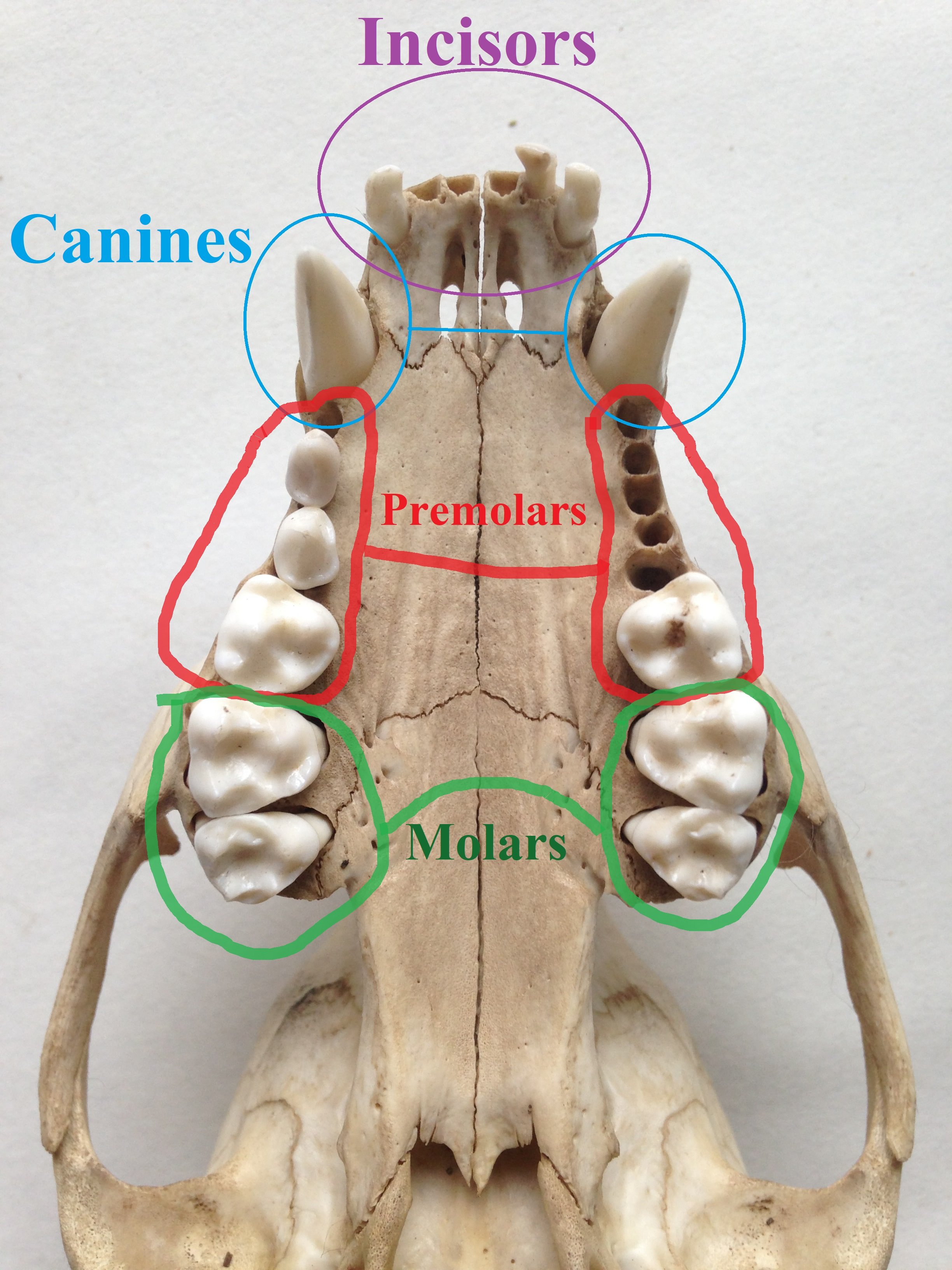

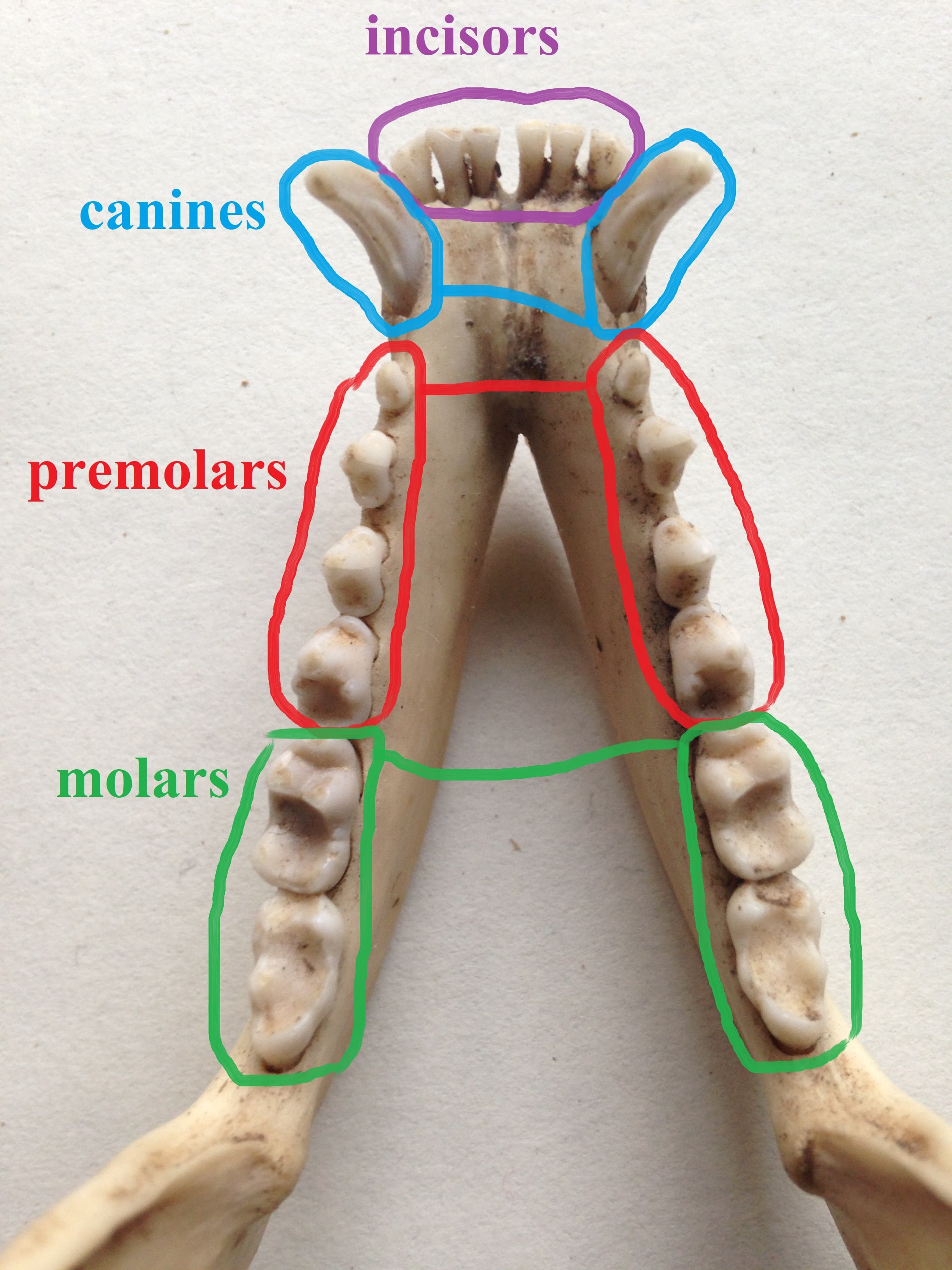

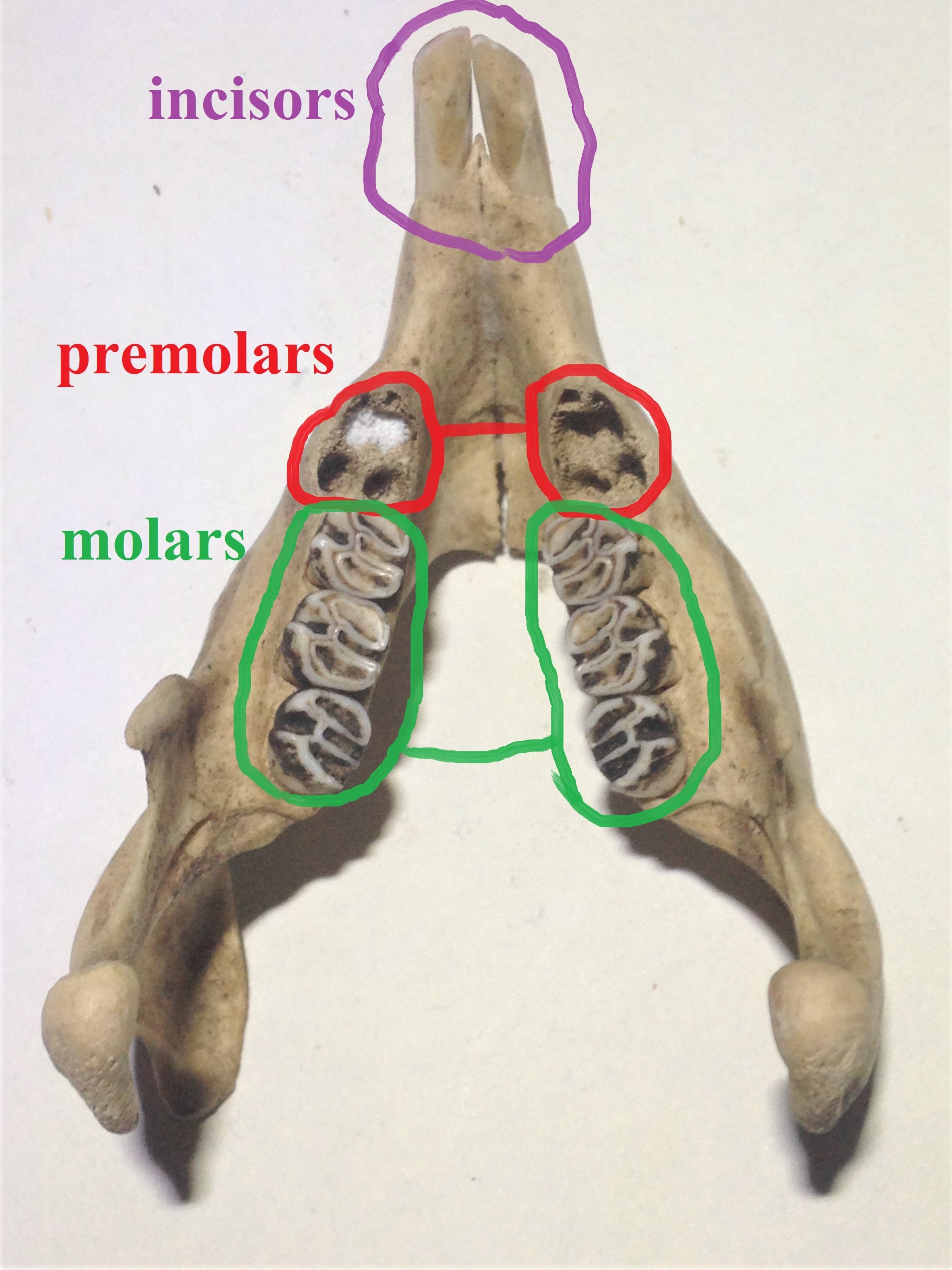

Raccoon (Procyon lotor) skull

I am so grateful to have a partner who is willing to sift through my writing and show me things I have overlooked or left out. One of the things that was pointed out to me recently was that in a previous post I assume that folks know what I am talking about in regards to dental formula on Red Foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and Coyotes (Canis latrans). I knew I was bored of writing in the last one and didn’t want to side track too much so I decided I would write a quick introduction to the teeth of mammals.

Skulls have a basic symmetry that extends also the teeth. What teeth we find on one side of the mouth, we will find those same teeth on the other side. For some mammals this symmetry extends to both the teeth within the cranium (on top) and to the teeth within the mandibles (bottom), but often this is not the case. Generally, carnivorous and omnivorous mammals have four kinds of teeth with each kind of tooth specializing in different functions. These different teeth are called incisors, canines, premolars, and molars. Some mammals lack some of these teeth, while some others have modified teeth that serve different functions.

“byron’s rule” states that it’s always a Raccoon (Procyon lotor) unless proven otherwise. This is because they are common and ubiquitous. It’s a good place to start as their skulls are often found and as omnivores their teeth can serve as examples for both herbivores and carnivores.

Incisors are located at the front of the mouth. They are thin, knife edged teeth specially designed for nipping, scraping, tearing and cutting. The word incisor comes from the Latin word incīdere “to cut, cut through, cut open; engrave”.

The canines are the big “vampire” teeth just behind the incisors. They are used by carnivores and omnivores to puncture, capture, hold and kill, while herbivores have very small canines or none at all.

Premolars and molars are for chewing, grinding, crushing, shearing and shredding. They are collectively called “cheek teeth”.

Mammalogists use a basic system for counting teeth. It is called a dental formula. To figure out the dental formula for a Raccoon we count the teeth along the top and bottom on one side, add up the total, and then multiply your total by two to account for the teeth on both sides. We count all the teeth that are supposed to be there, and if some are missing, we count them anyways. The purpose and goal is about identification of species, not an individual (we’ll get to that later). A Raccoon’s dental formula would start with the incisors, “i 3/3” as there are three incisors on the top of the mouth on one side, and three on the bottom of the mouth on the same side. We then move on to canines, written as “c 1/1” as the Raccoon has one canine on the top on one side, and one canine on the bottom on the same side. Premolars are written as “p 4/4” and molars are written as “m 2/2”.

So a Raccoon their dental formula would look like : i 3/3, c 1/1, p 4/4, m 2/2 = 40. This is helpful to start with, but remember that in nature variables happen all the time. We may find a Raccoon with an extra tooth, or missing one. Nature is wonderful like that.

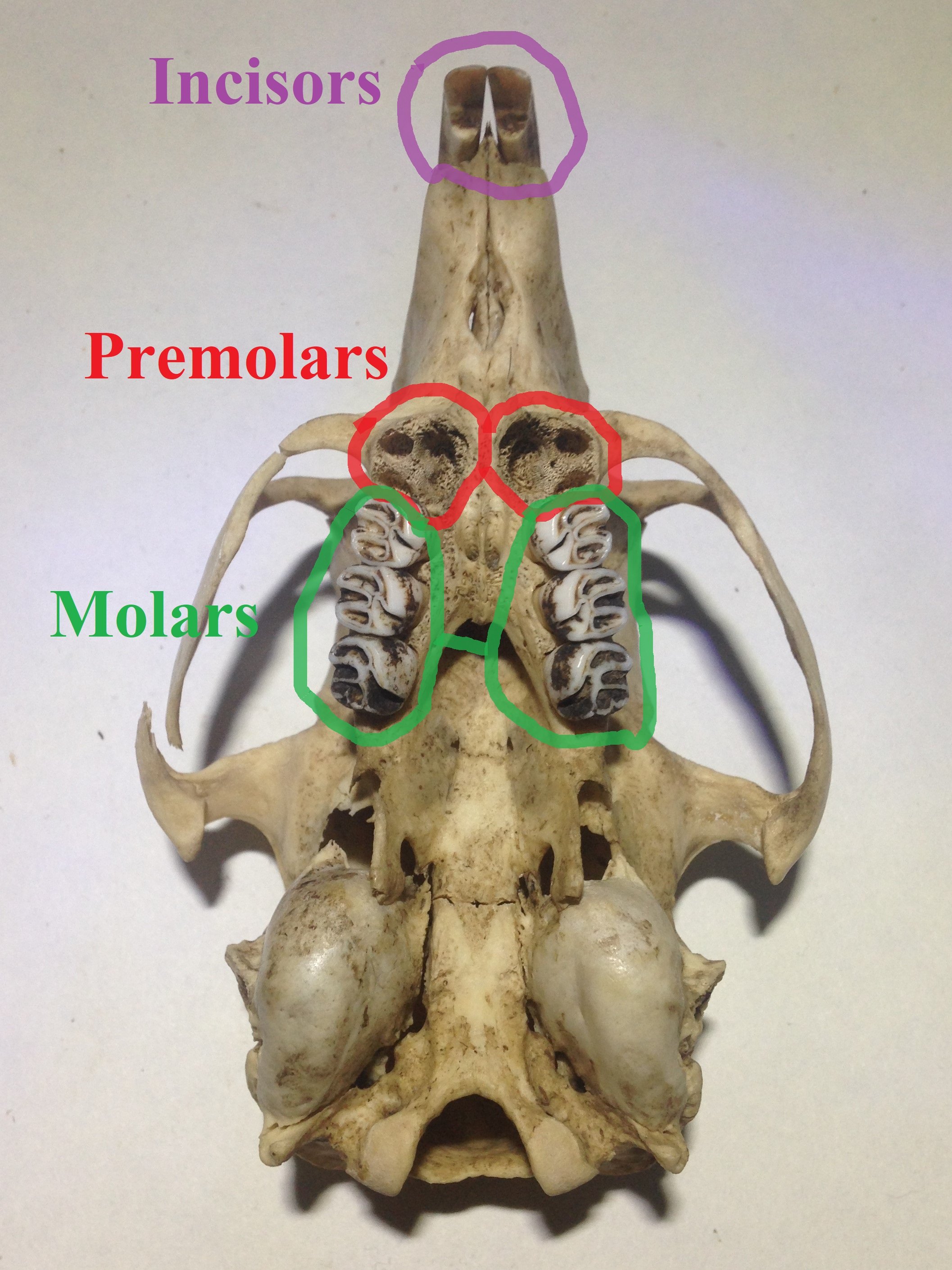

A Porcupine’s (Erethizon dorsatum) dental formula would look like i 1/1, c 0/0, p 1/1, m 3/3 = 20. Below are some images of the cranium teeth and mandible teeth. Note the massive incisors, the lack of canines and missing premolars (sometimes they get lost when cleaning a skull).

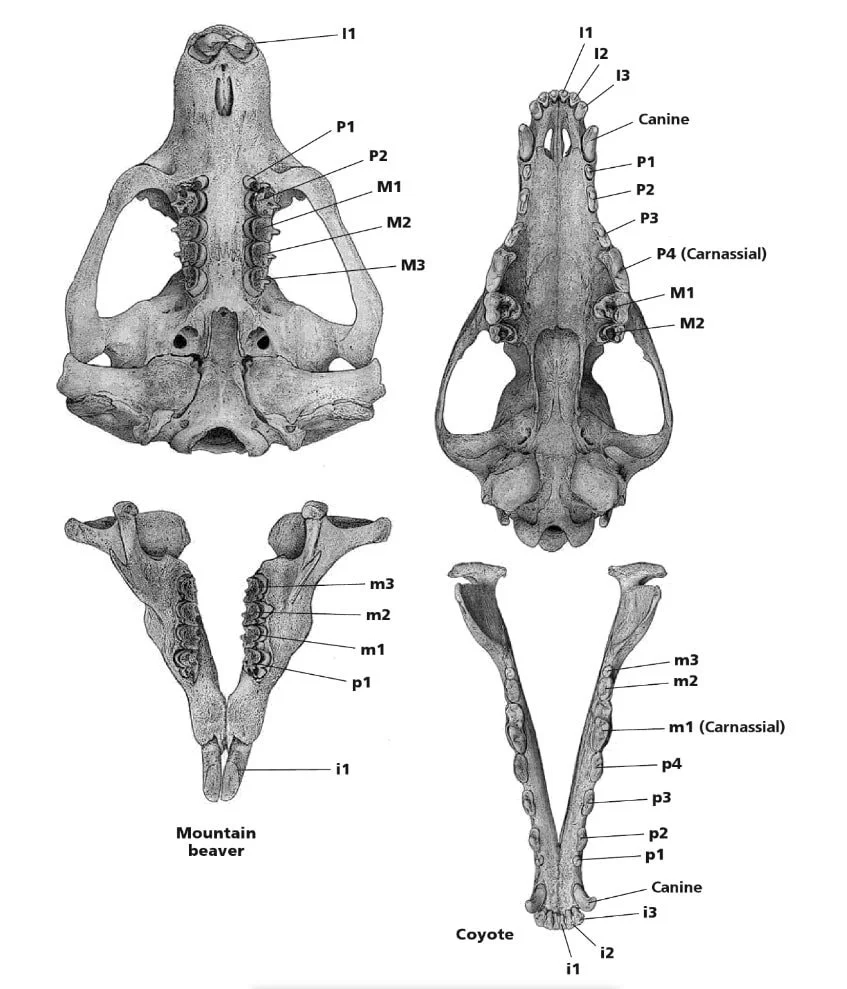

When we are describing individual teeth, the teeth are written in upper case for the teeth on top (I, C, P, M), and lower case for the teeth on the bottom (i, c, p, m). Once we have used our dentition formula to describe individual species, we can then name individual teeth by naming the teeth with the letter code (ie: P) and then adding a number of which premolar it is counting from the front of the mouth. So for the Porcupine skull above, tooth P1 is missing. I have found a couple of sources which also indicate which side of the mouth by using the capitals “L” and “R” for left and right, orienting to the subject animal. So for that Porcupine it would be RP1 which indicates the first premolar on right side of the cranium.

Diagram of individually named teeth from Mark Elbroch’s book Animal Skulls, from Stackpole Books, 2006.

The title above names all of this information as specific to non-human animals. For some reason, humans get their own special ways of recording dentition that dentists use that isn’t inline with mammalian nomenclature and zoological sciences. These human based systems can vary depending on where you are in the world as well. For example, canadian dentists have their own system, where as there is another universal system that appears to be used more globally.

When it comes to tracking teeth give a lot of information. We can look at bite marks into bone, flesh, bark, cambium, egg shells, fruit, and measure the distance between canines or the width of the incisors and this can help us determine who has taken the bite.

I remember a couple of times when I have found predated eggs, one time Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) eggs, another time, Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) eggs, and when looking at the eggs we took measurements of what appeared to be marks where the animal took the egg into their mouth, either for transporting the eggs or in the process of eating the contents. Measurements we about 25 mm across. Later, when I got home I measured some of my Raccoon skulls as Raccoon was my first guess and the measurements between the upper canines averaged out to 25 mm for an older Raccoon. It was helpful to have those skulls on hand to really check out the dentition and then to compare with the measurements I had previously made. Knowing the canine widths really helped to sort out who the likely predator was.

I know this post is pretty simple, but I’ll write another in the future that has more detail and more complexity. Perhaps it will expand on the teeth or maybe just cover more about skulls, as I seem to have a thing for them.

To learn more :

Animal Skulls by Mark Elbroch, Stackpole Books, 2006.

Example of the Canadian Numbering System for Teeth

Article on the Universal Numbering System for Teeth