Carrion Beetles pt. 1 : Nicrophorus tomentosus

I have been doing these simple walks with my partner in the evenings before we go home and get ready for bed lately. It’s been nice to just chill, go over the day, figure out what each other is up to the following day and to just spend a few minutes focused on each other… that is until I see something cool on the side of the trail.

2022.07.07

I just happened to catch a darker shape on the grass, and peered around my partner to get a better look. There it was, a freshly dead juvenile American Robin (Turdus migratorius). I had all sorts of assumptions of what had happened, like perhaps a Dog (Canis familiaris) had run up and got the young unexperienced bird while the bird was on the ground? I have seen it before. Or perhaps a Cat (Felis catus) did the same? Outdoor cats are consistently killing wildlife and this was a residential neighbourhood so this would also make a lot of sense. Oh, and I knew it was a juvenile from the dark spotting on the orange breast, and also the head looks like it isn’t as fat or big though this was more of a feeling.

After taking a bunch of photos of the dead Robin I flipped the carcass over to see if I could see any visible signs of trauma. I noticed a wound on the back of the neck, but I got totally distracted when a small orangey-yellow thing crawled deep into the grass.

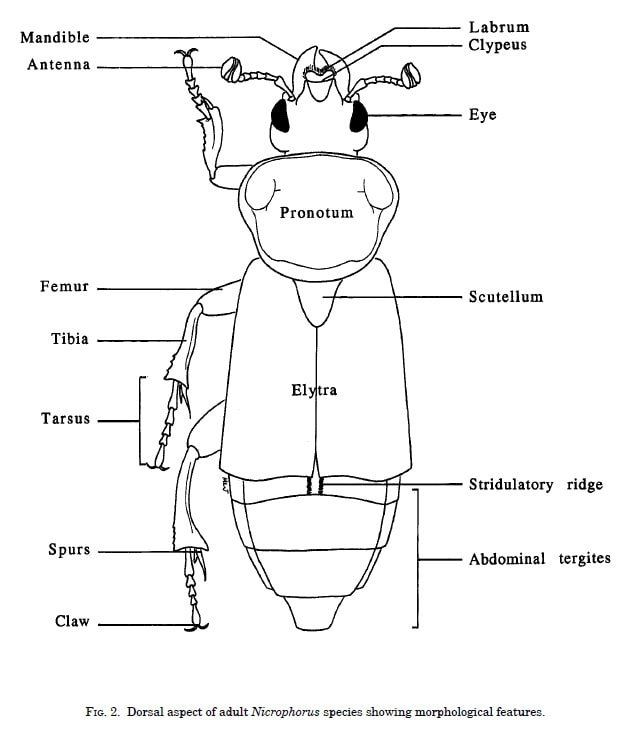

This was such a limited view of the animal, but I had a guess as to the family. I thought it was likely a Carrion Beetle (Silphidae) as they were crawling around near a dead bird, and suddenly trying to burrow down, as opposed to crawling away, when I moved the carcass, and their overall shape and size. But they looked different from the Carrion Beetles I most often see, the American Carrion Beetle (Necrophila americana). Instead this one had seemingly longer elytra (modified wings/wing covers) and the black Charlie Brown zig-zag and orangey-yellow Batmanish “Bat signals” patterns on the elytra. I ended up moving the grass enough to be able to pick up the beetle so I could take some photos. That obviously meant letting this animal, known and named for the fact that it crawls in and on dead things, crawl on my body. Yum.

Image from The Carrion Beetles of Nebraska by Brett C. Ratcliffe

All of the photos I got were blurry as this insect was certainly spooked and in a hurry. But the photos I did get allowed me to really see some extra details that I wouldn’t have got unless I euthanized them, which is kind of dumb if I don’t have to. I’d rather a blurry photo.

Anyhow, back to the identification. I really noticed the yellow fuzzy bit behind the head and this really helped with identification when I looked them up when I got home. The broad plate section that is covered with this yellow fuzz is called the pronotum and this species is actually named after the fuzzy stuff. They are Nicrophorus tomentosus which could translate to something like Short-haired (tomentosus) Death Carrier (Nicrophorus), which is a very metal name. A couple of common names for this species are Tomentose Burying Beetle or Gold-necked Burying Beetle. The name of the family group Silphidae possibly derives from the latin word “silva” meaning “woods”, “forest”, “branches and foliage of trees” (from Pocket Oxford Latin Dictionary, 1994).

I got to wondering a bunch of things while checking out this Short-haired Death Carrier Beetle as they crawled on my arm. Here are three standout questions:

Where do they hang out when there aren’t dead things around?

How do they find the dead things?

What are the conditions that make a dead thing suited for different species of Silphidae Beetles?

And here is what I know so far.

Where do they hang out when there aren’t dead things around?

This is a big one. I have no clue as of yet, but I am still searching this one out. It seems most of the studies and research into the lives of the Nicrophorus beetles is done at baited traps and no one, including me, has taken the time to follow one of these beetles around after they are through with the carcass.

“The habits of Silphid beetles are unusual and have not been entirely observed.”

- from the book Forensic Entomology: The Utility of Arthropods in Legal Investigations (CRC Press, 2001)

One paper I found on habitat uses by Silphidae Beetles says that N. tomentosus is a habitat generalist, with a broad range of habitat types they prefer. So could the answer to the question above be… everywhere? This answer helps refine the question for me. I am really wondering where in specific do they hang out.. in the soil? Clayey or sandy soils? Wet or dry soils? What about tree bark? Or leaf litter? Deciduous or coniferous leaf litter? Would there be just as many N. tomentosus in a mature mixed Maple-Beech forest as might be found in a younger White Pine (Pinus strobus) plantation? Maybe a generalist is just a generalist and that does just mean everywhere.

Dead Nicrophorus tomentosus found near a dead Short-tailed Shrew (Blarina brevicauda), on the Eramosa River Trail, 2022.08.26

How do they find the dead things?

There are receptors on the antennae that help the Beetle to smell the chemicals which are being given off the dead creature. One of the chemicals is hydrogen sulfide which is released into the air as dead animals decomposes. Hydrogen Sulfide also comes from decaying organic matter such as leaves and feces.

What are the conditions that make a dead thing suited for different species of Silphidae Beetles?

It seems like different species within the Silphidae family will colonize the carrion at different stages of decomposition. There are five stages of decomposition : fresh, bloated, active decay, advanced decay and dry (not to be confused with the 8 stages of death). I have read that the Nicrophoroni subfamily (which the Nicrophorus tomentosus is a member) of Silphidae Beetles will colonize the carrion during the fresh stage so they don’t have to compete with other animals, such as flies and their larval maggots. This seems to align with my finding the Beetle on a freshly dead corpse rather than a rotting one. Again this points to N. tomentosus as being a useful species in forensics (check out the section on Blowfly larva near the end of this tracking journal).

I also read that the Silphinae subfamily are more often found on larger carcasses, while the members of the Nicrophorinae subfamily prefer to feed on smaller corpses, such as rodents and birds. Again this was confirmed with my experience with the dead Robin.

Many adult members of the Nicrophorous genus bury small animal carcasses where they then lay their eggs, hence another common name for this group of Beetles as “Burying Beetles”. However, N. tomentosus adults don’t actually bury the corpses they find. Instead they crawl beneath the dead animal and begin to remove soil from under the death thing so that it sinks into the excavation. They then cover the freshly dug pit with leaf litter and surface debris. The larvae feed on the carcass and pupate in the adjacent soil while the adults defend the larva and feed on the maggots of flies.

Overall it was awesome to find the dead juvenile Robin, and to get to meet a new Carrion Beetle whom I did not know before. As always is the case, I have some things I wish to do different in the future. I really wish I had returned to the Robin the next day see if if any pit had been dug. This would be great to photograph for future tracking reference, and also as a possible sign to look for as an indicator of where to collect small vertebrate animal bones. Luckily, there will be more dead stuff to find and more Carrion Beetles to encounter.

To learn more :

Habitat use of co-occurring burying beetles (genus Nicrophorus) in southeastern Ontario, Canada

Better image of N. tomentosus from Bugguide.net

The Carrion Beetles of Nebraska by Brett C. Racliffe