A Side Trot On My Driveway

I had stepped outside to take out the recycling when I noticed two canid trails on my driveway. There was one leading towards the back yard, and one heading back out towards the street.

Two trails in my driveway. A side trot in the middle of the photo heading away from the camera, and a direct register trot on the right side of the photo coming towards the camera.

I took a closer look to try and see which species it may have been, as I have noted Domestic Dogs (Canis familiaris), Red Foxes (Vulpes vulpes), and Coyotes (Canis latrans) in the area on other occasions and wouldn’t have been too surprised to have seen any of these going in to my backyard in search of play or prey.

Two canid tracks, front closer to the bottom of the photo, hind closer to the top, in a side trot gait pattern.

One of the first things I noted were the toes and how narrow and pointed they looked. Sure they are rounded, but they appear like bullets in my mind. This reminded me of a Red Fox because their feet are furred, especially in Winter, and this can diminish the area of the toes which registers in the snow. I also didn’t notice any clear signs of claws in the tracks above. This could’ve been because of the substrate, but perhaps it was because of something else. Red Foxes have semi-retractable claws on all their toes except for the dew claws further up the front legs so this could be another point that these trails were left by a Red Fox. I also noted the heel pads. The heel pad on the front foot (at the bottom of the photo) is pretty straight and narrow. For a Red Fox the heel pad can appear like this, or as a thin straight line, depending on how much fur is covering the heel pad. The heel pad of the hind foot (track closer to the top of the page) appears as a small dot, similar to a thumb print and again this could be due to fur on the foot blurring out the heel pad, which is a common trait of a Red Fox.

So yeah, I thought this was a Red Fox. But what about the gait, the “side trot”?

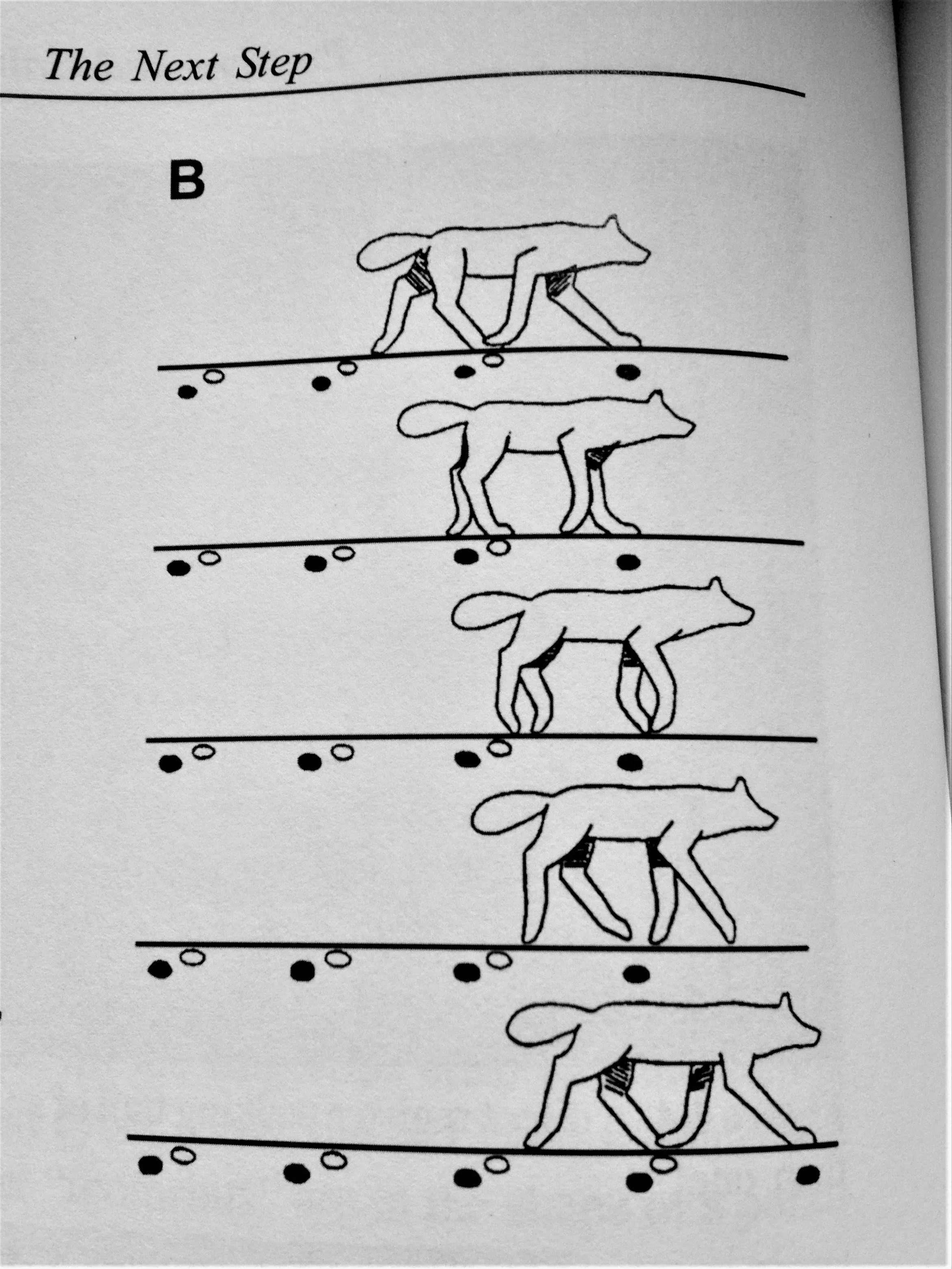

The image to the right shows the trail of the Fox in a side trot gait, which is described as a group of two tracks, with the front foot sitting just below and to the side of the smaller hind track, which is just ahead. When a Fox, or any canid is moving in this gait, the back end of the animal angles a little to the side so that the hind feet travel outside the midline of the animal, where the front feet would land, in order that they can fully extend their legs without striking the back of the front legs. This gait is a little faster than a conventional trot and the greater the overstep of the hind beyond the fronts, the faster the Fox is moving. This means that I could measure the distance between each group of two tracks and if the measurement is getting longer, then that would indicate that the Fox is reaching more, thus gaining more speed enabling them to do so.

I often see these side trot gaits when animals are making their way quickly through a flat open areas where is less of a need for the slight vertical bounce that comes with a direct register trot. For a direct register trot, the animal needs a moment of suspension when switching out the front feet and placing the hinds where the fronts had just been (check back soon for an entry on direct register trots). Since the terrain is flat, and the hind feet are landing beyond, and to the side of the fronts, as opposed to within the same spot, a side trot can denote a lower horizontal body position when the Fox is moving.

In his book “The Next Step”, David Brown describes the side trot as a “displaced trot” and goes into a lot of detail around energy efficiency of this gait versus other “aligned gaits”.

These displaced patterns… reflect a gait where the animal is stressing the horizontal component over the vertical. Because this gait has a very low arc of stride and energy is not wasted pushing upwards, it is more efficient than many of the aligned strides. Its drawback is that, because it is not very fast, it is not useful for chasing or escaping. Furthermore, it will not carry the animal over irregularities of softness in the surface. An animal attempting to use a displaced trot through untracked forest would trip over tree roots and fallen limbs while trying the same thing in soft snow would require a lot of plowing through and would quickly exhaust the animal.

Diagram depicting the sequence of foot falls in a side trot, from David Brown’s book “The Next Step”.

I would interpret the trail along my driveway as the Fox was done checking out the backyard and since they weren’t likely to spook any potential prey on the way out that they wouldn’t have on the way in but instead could just book it.

A possible note about side trots is that some folks think you can determine the direction the animal is looking in based on which side of the trail the hind feet are landing on. I am unsure this is true, but if this were, the Fox would intently be looking to the left, towards the side of my house, where mice often hide in the garden. I have read both assertions of this and rejections, but with a quick glance of my books, I can’t seem to find anything at hand which leans one way or the other.

In the first edition of Mammal Tracks and Sign by Mark Elbroch, he included a series of Coyote trail patterns, alongside possible interpretations of them. I believe many of these would also apply for a Red Fox. Here is the description he provides for a side trot:

Side trot. Travel mode: This gait may indicate that a coyote has a destination in mind and has picked up the pace slightly. It is often seen on easier travel routes, such as beaches, roads, and trail systems. Increased awareness: Thi gait is often usd when coyotes are exposed and away from cover, or between areas of cover, but not yet in full alarm. Trespassing coyotes might also pick up their pace when moving through another pack’s territory.

I think showing visually how a side trot works will help my description make a little more sense. Here is an excerpt from a video by educator Steve Leckman on animal gaits:

To learn more :

The Next Step by David Brown, McDonald and Woodward Publishing Company; Illustrated edition, 2016

Mammal Tracks and Sign by Mark Elbroch, Stackpole Books, First edition, 2003

Steve Leckman’s Animal Gaits video on youtube