Tracking Journal Jan 01, 2021

There were familiarities and mysteries while out tracking with Carolyn today. She asked if I wanted to go check out a some Hemlocks (Tsuga canadensis) she knew and I, as per usual, was down. She picked me up and on route she asked if we should go look at the Beavers (Castor canadensis) she’d been visiting with her family. Again, I was down.

The snow was really crunchy along the walk towards the pond. It had been warm with a high of 4°C and it had rained a couple of days before (Dec 30), and the frozen again and stayed around 0°C on the 31st. The Moon had been full on the 29th, but had been mostly cloudy or overcast over the past few nights. It was probably around 0°C when we went out.

At the pond we saw that it was frozen over, which got me wondering about how Beavers deal with a frozen pond - do they break through the ice somehow? Use an escape hatch in the lodges? Maintain an ice free hole like Seals do? I still havn’t looked it up, but I’m sure I will.

UPDATE: Turns out the Beavers live under the ice, within their lodges for most of the Winter unless there is some sort of mid-Winter melt. According to Mary Holland from Naturally Curious, Beavers will only venture out to poop, to mate, and to eat. Pretty much like me on some of these Winter days.

Thanks Carolyn for looking it up!

We started looking at the chews along the edge of the pond. I was attracted to the big Sycamore (Platanus occidentalis) and the work the Beavers had done at the base. The trees were pretty wide so there was no sign of them trying to really dig into them, and they weren’t entirely girdled so I’ll have to go back sometime in the spring/summer and see how they do. The incisor scrapes on the tree in the first photo were between 5 - 6 mm for each tooth, which is additional confirmation as this falls within the range of a Beaver (4.65 - 7.98 mm according to “Animal Skulls” book by Mark Elbroch). I had never seen Beavers chew on Sycamore before, but I only have limited experience. They had also been mowing down on the Silver Maples (Acer saccharinum) along the edge of the pond as well.

While looking around at the Beaver sign I saw a fungus that I was curious about, the first of a few.

Unknown fungus on Silver Maple

I have seen this fungus before on Buckthorns (Rhamnus cathartica) and wondered at it for a while, but never looked into it. I have looked in my books on tree pathology, though they aren’t too in depth and I only have a couple old ones. I have also posted it to the mycology subreddit in hopes that someone on there can help me with the correct i.d.

UPDATE: Lots of folks have been weighing on on this (some even have called it a lichen), but I am now torn between Irpex lacteus and a Corticioid fungus. What do you think?

A canker of some sort growing on the same Silver Maple

We also noticed this canker growing on the Silver Maple. It looks to me like either Eutypella parasitica, otherwise known as the Cobra-head Canker, or Nectria galligena, Nectria Hardwood Canker. As far as I can tell, they present similarly, and both can parasitiz Silver Maples. The fungus (the scientific name is for the fungus, not the action the fungus has on the tree) usually affects the trunk or limbs of the tree. It may kill smaller trees (anything smaller than 12 cm Diameter at breast height, or around 1.3 m (4.3 ft) above the ground), but usually the bigger trees aren’t killed by it. However, the canker makes for an area of the tree which is prone to decay and destabilizes the trunk making that spot prone to breaking in the wind. I tend to see the cankers around but only learned about them this summer.

Carolyn and I began moving along, but we only got a little bit away when I noticed a hole in the snow leading down to the water. I looked a little more carefully and discovered a scat!

The scat measured 5 mm D at the widest point but I didn’t get the length. It was long, twisted, tappering towards a point at the end, with a bit of a curled tail. First thing I thought of was Weasel. I still think Weasel, but in examining the scat I can’t be certain as to which Weasel. Sure it was by a hole at the edge of a pond, which led down to the water, which could be a sign of Mink (Neovison vison) perhaps? Or maybe it was an Short-Tailed Weasel/Ermine (Mustela erminea) or a Long-Tailed Weasel (Mustela frenata), who’se scat sizes fit a little bit better with the measurements. A little bit beside the scat, at the mouth of the hole, there was another little remnant,which reminded me of what I saw recently on a Mink trail beside another hole into the snow. When I researched about these remains near scats I learned that Least Weasel (Mustela nivalis), Short-Tailed, Long-Tailed, and Mink all have this habit that after they deposit their scat, they spread their hind legs, getting their butts low, and then drag them on the ground to leave some scent behind (or maybe they are just wiping their butts?). Perhaps this is the sign of that action occuring?

We also found a hair amidst this little remnant piece at the mouth of the hole. I got to wondering if this was a hair from the possible Weasel or if it was hair from prey the Weasel had eaten?

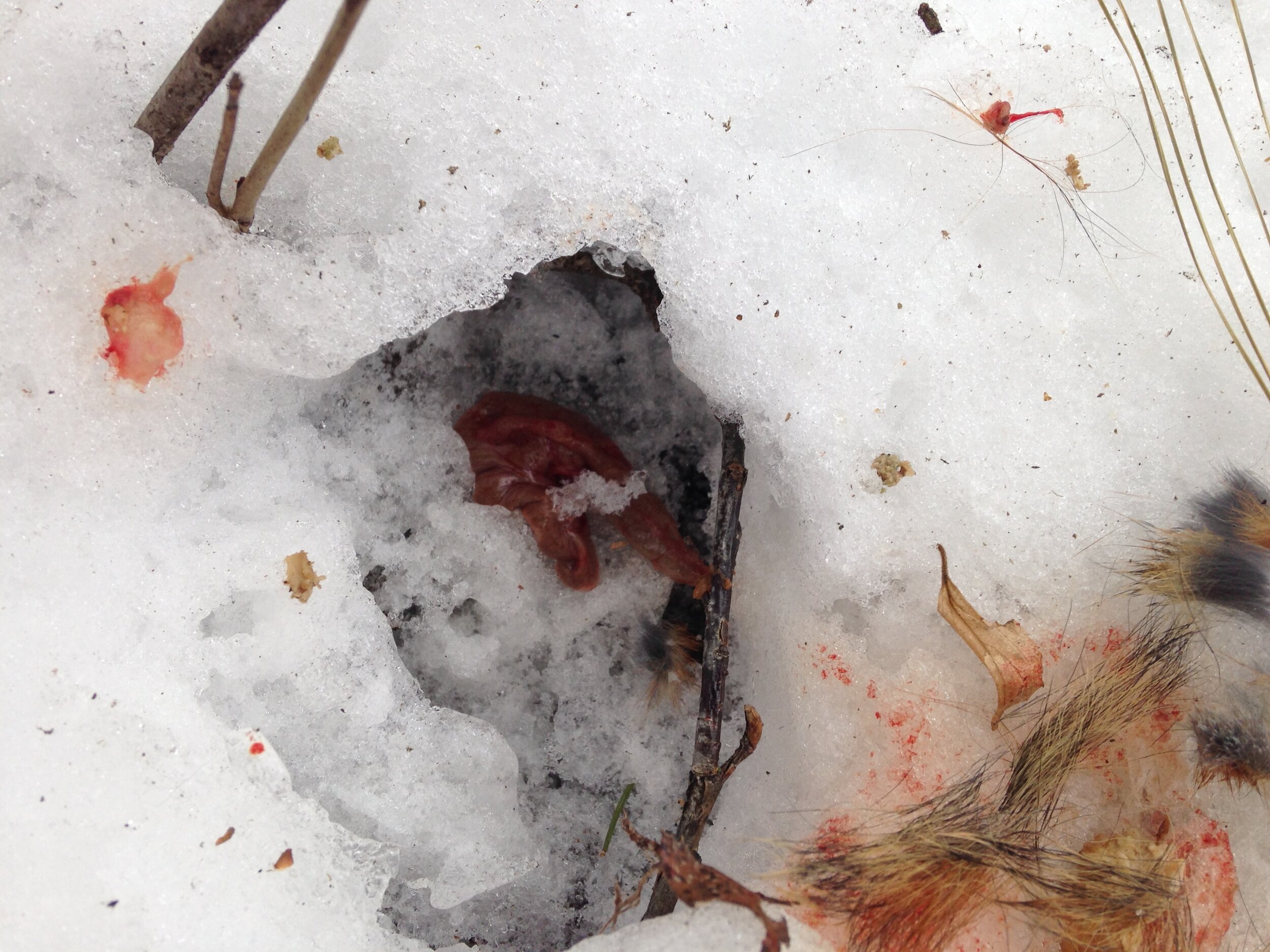

A little ways along on our trail up from the Weasel scat, and by little ways, I mean maybe 7 m, Carolyn found a killsite. We both decided it was an Eastern Cottontail Rabbit (Sylvilagus floridanus) that had been eaten but we weren’t sure who got the Rabbit? Was it that Weasel? Was it someone else?

I am going to post a more detailed analysis of an Eastern Cottontail kill site in a couple of days, but for now my big question is just what part of the Rabbit is that organ in the 3rd and 4th image? I have so many photos of dead Rabbit bits from various killsites over the past few years, that it would be fun to piece together a blog post on the innerds of a Rabbit detailing the names, positions, and functions of the internal organs of an Eastern Cottontail Rabbit. Would you read that post?

Nest along the road

We walked on, discussing how to teach these days when classes and structures of classes are changing, how we can best encourage connections with the landbase as well as meet the needs of the modern near ‘nature’ impaired culture. While walking we noticed a couple of cool things. One being an Eastern Bluebird, which after researching, I’ve learned are uncommon, but present around these parts in Winter, but also we found a nest. I have been trying to learn about nests better so we stopped to give it a look, make some notes and take some measurements.

Overall height from ground : 157 cm (~62 in)

Overall diameter : 11 - 12 cm (~4.5 in)

Overall height : 8 cm (3 1/8 in)

Cup depth : 4 cm (1 9/16 in)

We found the nest at edge of a forest close by to a wetland, woven between vines, likely Virginia Creeper (Parthenosissis quinquefolia) or Grape (Vitis spp.). The nest was loosely woven and loose to touch. Felt fragile, but not like a Mourning Dove nest. There were no leaves within the construction of the nest, though there was what looked to be a Buckthorn leaf and Cedar (Thuja occidentalis) leaf which had fallen in. The nest was seemingly just constructed of small fine twigs, with a little grass lining the bottom of the cup. There didn’t appear to be any mud or soil, and there were pieces of plastic and Birch (Betula spp.) bark woven within on the bottom.

I am unsure about this one. The vines seemed flimsy and unlikely that they could have supported a nest with an adult bird, and eggs within, plus it was so close to the sidewalk, right beside a very busy road. I bet this nest was never used, but instead initially constructed quickly and then the bird got a real idea of what traffic would look like, what kind of weight the vines could hold and then ditched it and built somewhere else. It brings up questions for me as to when do American Robins (Turdus migratorious) start mudding their nests? Do they do it as they build or afterwards as a reinforcing technique?

We walked away talking about best guesses, but none of them felt right.

We continued on our quest, looking down for tracks, up for signs of Porcupines (Erethizon dorsatum), both of which we found and while doing so came to the Hemlock trees. I get excited by Hemlocks. I still am not sure why, but they seem novel and different. Something about them reaches into me. I don’t have too much experience with them, but really like collecting the branches that Porky’s let fall and then I make tea from the needles. I feel like we’re sharing the bounty. Hemlock needles taste great and feel generally warming, and I bet in Traditional Chinese Medicine that would be their action.

While looking at the Hemlocks we noticed that the barks of many were discoloured. Not all of them, but a few of them had pale blue-green hue to the bark, or an orangey-red look.

I had wondered about the orangey hue for a long time. I remember a couple of years ago seeing it on a tree along the Bruce Trail with my friend Matt. We wondered at it for a while and I told myself I would look it up when I got home. A couple years later, March 2020, before the pandemic really struck close to home, I was out with the tracking apprenticeship and we were wondering about it again, this time seeing it on some trees at the Krug Forest Preserve near Kinghurst, Ontario. Today I even found an audio memo where I was wondering aloud with our apprenticeship crew about it. Today I decided to look it up once and for all.

I think the orangey stuff is Trentepohlia, which I have learned is a free living green algae which grows on rocks and trees. Sometimes it grows with fungi in symbiotic relationships as Lichens. The orange colour comes from large amounts of carotenoids, the same sort of pigments that makes Carrots (Daucus carrota subsp. sativus) and autumn leaves orange. The carotenoids are so abundant that it hides the chlorophyll that would other render the Trentepohlia green. One neat thing I learned about is that where I found it, it was mostly growing on the North side of the trees, likely to be out of the sun which would dry out the algae too much. I have linked to a paper at the end of this entry if you want to learn more.

As for the blue hue, perhaps it is the same algae but with less carotenoids so that the greeny blue comes out a little bit stronger?

Around the big orange Hemlocks we decided to do a sit spot. We had found a tree that looked like it may be housing a Porcupine and Carolyn decided to hang out and see if the Porky would emerge. I tucked under a fallen tree hoping to see a Mouse (Peromyscus spp.) crawling around through the roots. I saw nothing, but Carolyn did see the Porky stick their head out of the hole a couple of times and appear to look at her. She was stoked!

We began walking back to the car and just happened across a couple of women on the trail in front of us, one of whom had a Gyrfalcon (Falco rusticolus) on her wrist. I wasn’t expecting this, but I am not surprised. I once interviewed a couple of folks from WILD ONTARIO who are based out of the Arboretum at the University of Guelph where we were parked, and sometimes the volunteers bring the birds out just so they don’t get bored and can acclimatize to meeting new people as they walk by. It was a great way to end a fun walk with a good friend.

Bonus “Lady with a Gyrfalcon” photo. I don’t know the lady’s name, but Ellesmere is the Gyrfalcon.

More info:

Red Bark Phenomenon - Eastern White Pine Eastern Hemlock In Connecticut and Massachusetts, there have been many recent observations of a novel condition which causes intense reddish orange coloration of tree bark, termed here for the first time as the red bark phenomenon (RBP).